Report

Storytelling for Systems Change: Listening to Understand

Thea Snow and Asitha Bandaranayaka (Centre for Public Impact)Rachel Fyfe (Dusseldorp Forum) Lila Wolff (Hands Up Mallee)

“Stories, in their many shapes and forms, are a part of human nature and humans are immersed in them: they are experienced as deeply individual and as integral to relationships between people; they provide explanations, meaning, and entertainment; people die for them, and people dismiss them as trivial; they enlighten and obscure; they enable judgement and reasoning and they seduce, persuade, and distort. We show that, by holding on, it is possible to listen to stories for the narrative evidence they provide, the cognitive value they possess, and the important ways in which they can enrich public reasoning”

Sarah Dillon and Claire Craig

Acknowledgement

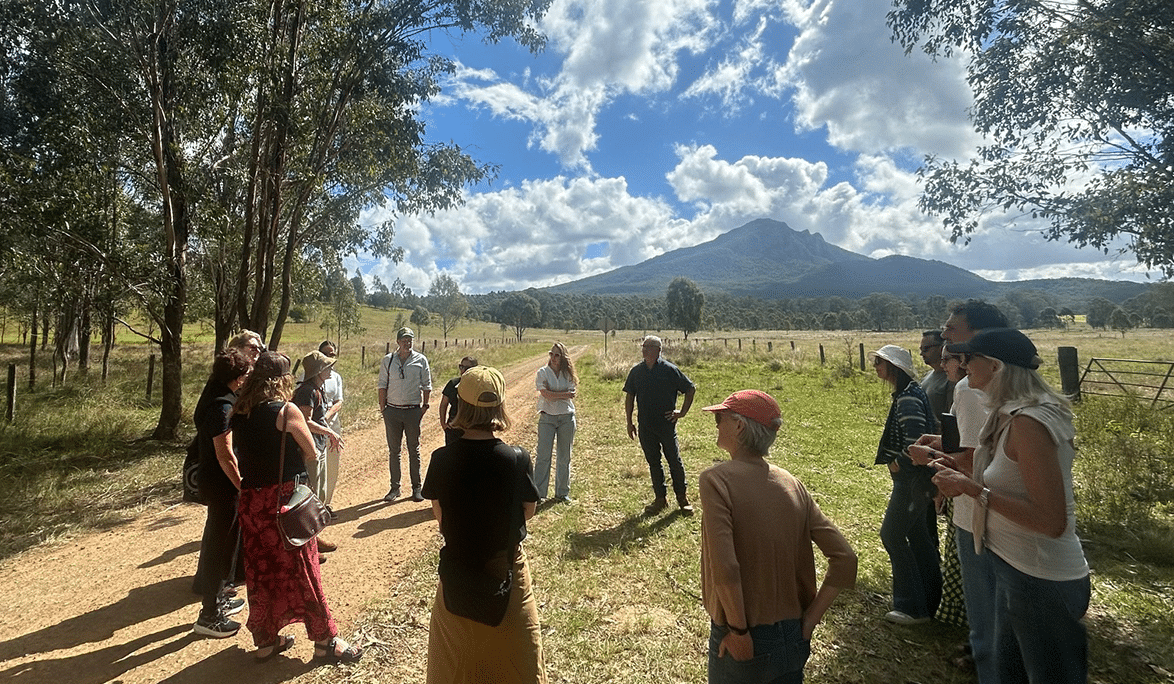

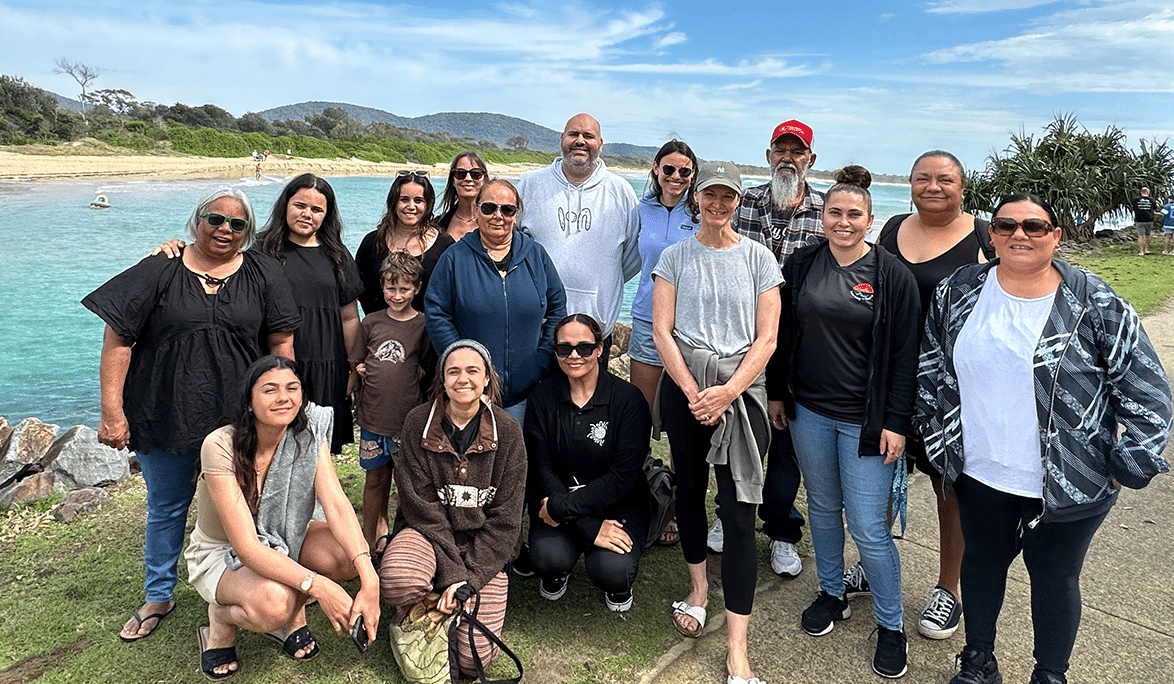

We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which this project was created, and pay respects to Elders past and present. We also acknowledge First Nations’ ancient connection to storytelling and how it shapes our world and our connections to it.

This second phase of our Storytelling for Systems Change work would not be what it is without the contributions of many. See the names of everyone who contributed.

chapter 1: Our Invitation

This report doesn’t begin with an executive summary. It doesn’t have one at all. Instead, it begins with an invitation for you, our readers, to engage with the following pages in whatever way feels right to you.

You may want to read this from start to finish, and that’s fine. Or, you may want to engage with the report using a less linear approach, focusing on what resonates most with you.

We have resisted summarising our findings into a single page because that’s what we heard good listening asks of us. Good listening asks us to avoid simplifying stories in order to fit neatly into a public-facing document.

We heard that when people listen to understand, they listen in a way which can hold tensions and contradictions. More often than not, executive summaries smooth over these tensions to pull out pithy key messages. We want to resist this.

We know that our decisions as authors matter. What we feature, exclude, and how we order and present the information is all an exercise of power. We want to try to subvert the traditional power dynamics as much as possible (noting, of course, that this is still very far from perfect).

We want to offer you insights into what we learned in a way that doesn’t centre us as authors, but centres the voices we heard, as well as those who are reading it. So, we invite you to dive in and explore as you want.

We offer suggestions at various points about where you may want to move to next. Of course, you may want to choose a different path altogether.

Each of you will bring your own perspectives to this report, agreeing strongly with some points while hopefully disagreeing with others. These differences are enormously valuable.

We hope you enjoy exploring the insights that follow as much as we have.

chapter 2: The story of how we got here

The seeds of this story were planted in 2021. They were planted in the rich soil of an observation from Teya Dusseldorp, Executive Director of the Dusseldorp Forum:

“I work with communities who are engaged in inspiring systems change work. Yet, so few of their stories are being heard. I want to understand why and support them to tell their stories more effectively.”

From these original seeds, a seedling grew, which needed tending and nurturing. And so emerged a partnership between the Centre for Public Impact, Dusseldorp Forum, and Hands Up Mallee, who agreed to work together to explore what these seeds might become.

As the seeds were nurtured, several branches began to grow. We called the first of these branches Storytelling for Systems Change: Insights from the Field. This branch offered a range of insights. We learned that stories can be used to change a system, as well as to evaluate, understand, and showcase the change occurring in communities. We also heard that stories require different approaches – stories that attempt to enable change look different to those seeking to celebrate change.

We learned that great stories privilege the voice of the storyholder; are resonant, clear, and relatable; and are guided and bound by agreed protocols. However, we also heard that technical, structural, and institutional barriers can hinder good storytelling.

In addition to offering insights, this branch also surfaced some questions. One question stood out to us – how might we increase the number of funders and enablers (from government and philanthropy) ready and willing to hear and respond to the stories that communities are telling?

This felt like a critical question. We know that to have an impact, stories need to be heard. So what does it take to create the conditions where people in government and philanthropy are able to listen deeply? As Fiona Merlin, Measurement Evaluation and Learning Coordinator from the Hands Up Mallee Backbone team, asked: how can we cultivate an audience who “listen to understand?”

This question catalysed the growth of this new branch in a different but related direction – a branch which explores “storylistening” in more depth. What follows is our attempts to gather and share what we’ve heard.

- If you want to understand how we define “stories” and “listening”, move to the next page.

- If you want to learn more about our ways of working, skip to how we worked.

- If you’re keen to get straight into the findings, jump ahead to what we heard.

chapter 3: What do we mean by stories?

Our first phase of work did not offer a formal definition of stories based on the academic literature. That’s because we wanted our conversations to define stories for us.

Similarly for this branch, we have tried to resist being drawn too deeply into the tangle of literature which defines stories (and storytelling and narrative) in many ways. As Sarah Dillon and Claire Craig highlight in their book Storylistening: Narrative Evidence and Public Reasoning, “Wide-ranging reading reveals no consistency in the use of ‘narrative’ versus ‘story’ across disciplineand sectors.”

However, we noticed that in many of our conversations, people used the terms “stories” and “qualitative data” interchangeably. For us, they mean something different, and this distinction is worth exploring.

As we see it, the key difference between qualitative data and stories rests in where power sits. In the context of qualitative data, researchers shape the questions and decide how they will be asked, analysed, and interpreted. As Dave Snowden, founder of The Cynefin Co. explained, “In qualitative data, whoever is asking the question owns the story.” In the context of storytelling, however, the storyholder decides which stories to tell and how to tell them. Perhaps most importantly, the storyholder owns the interpretation of their stories and observations.

Participatory research approaches, such as Most Significant Change and Participatory Narrative Inquiry, go some way to addressing the power imbalances in qualitative approaches. However, many would argue that this is not enough. Dave Snowden pointed out that as soon as you ask someone to tell a story in an environment other than their own, you’ve changed their story. For this reason, he suggested that we need to involve those telling their stories in the gathering process, and “we need to listen to the stories being told in the street, not the stories being told in workshops.” While this may not always be possible, working to ensure that the locus of power sits with the storyholder, rather than the researcher, appears to be a key feature of effective story work.

One final thing to note is Cynthia Kurtz’s observation that the word “storytelling” in the report title is imperfect. Cynthia emphasised that “storytelling does not change systems. The universe of manifold interactions that surrounds stories changes systems…Calling the entire world of stories storytelling is like calling the water cycle rain. It’s so much bigger than that.” We agree. And we hope what we’ve written here goes some way to engaging with the important nuances that Cynthia highlights.

If you want to spend more time reading about styles of listening, move to the next page.

If you’re interested in learning more about our methodology, skip to how we worked.

If you’d prefer to move straight into what we learned, head there now.

chapter 4: What do we mean by listening?

Just as there is a vast literature on stories and storytelling, a lot has been written about different styles of listening. Again, we have chosen not to delve too deeply into this literature. And yet, we have deliberately called this branch of work Listening to Understand. So, what do we mean by listening?

chapter 5: The forest (the resources we drew from)

We want to acknowledge the rich forest of resources we have drawn from to shape this work.

We focussed most of our attention on the insights generated through conversations and workshops. However, we have also drawn on the vast literature and expertise that already exists, seeing our fledgling tree as one amidst many.

This includes:

- Storylistening: Narrative Evidence and Public Reasoning – Claire Craig and Sarah Dillon

- Participatory Narrative Inquiry – Cynthia Kurtz

- Sheep Farming After Chernobyl – Brian Wynne

- Listening as a Form of Healing – Jennifer Brandel

If these resources feel like enough for now, move to the next page to learn more about how we worked or skip straight onto what we heard.

If you want to see what other resources we drew on, jump to the resources list.

chapter 6: How we worked

An essential part of this work is not just what we discovered but how we went about discovering it. We sought to create ways of working that were open and inclusive, sharing our learning, mistakes, and emerging insights.

We shared Storytelling Digests, which provided regular updates to everyone who gave their time to the listening sessions. We also invited everyone who participated in a listening session to a sensemaking workshop where we collectively identified key themes and insights. And finally, as we did for the first branch of this work, we shared an early draft of this report with everyone who contributed, inviting them to ask questions, offer comments, and highlight points we had either missed or misconstrued.

Like last time, we met weekly as a project team to deepen our relationships and share our journey of discovery. We also spent time upfront defining how we wanted to work together as a team and created a Team Charter to support this.

Whereas the first phase of this work focussed on listening to storytelling experts and those in community, this time we concentrated on speaking to people in government, philanthropy, and academia. We also extended an invitation to anyone interested in joining us for a group listening session, which introduced a richer diversity of voices and perspectives.

Finally, a key insight from our listening work was the importance of holding contradictions in stories rather than trying to smooth them out. We have tried to honour that approach in this report. For this reason, there will be tensions in what you read and not everything we explore will feel neatly resolved. This mirrors the richness and complexity of stories.

chapter 7: Team charter

As a team we value curiosity and new perspectives. In practice this looks like:

- Asking questions of our partners, interviewees and of ourselves about why things are done a certain way, and what the underlying assumptions are

- Encouraging diverse perspectives by actively seeking input from people with intersectionality and difference in backgrounds and experience

- Embracing uncertainty through a commitment to adapting our approach based on what emerges

- Being deliberately (but carefully) subversive by challenging stereotypes and pushing governments and funders beyond their comfort zones

As a team we value equity and inclusion. In practice this looks like:

- Elevating the voices of storytellers

- Avoiding exclusionary practices and reinforcing stereotypes

- Incorporating diverse perspectives

- Sharing our findings in different ways – for example through a micro-podcast, or perhaps engaging an artist

As a team we are committed to the idea that the process is as important as the product. In practice this looks like:

- We are learning new things as a team and having fun

- We prioritise coming together as a team through weekly meetings and (hopefully) a babka-eating session

- Working in the open, through blogs, regular digests etc

- Using listening sessions and workshops as a way of catalysing new conversations and connections amongst participants

We want this work to contribute to meaningful change. In practice this looks like:

- Creating something that people value and use because it is clear and easy to understand and share

- Generating valuable, inspiring and enlightening insights

- Creating something that makes people feel hopeful and aspirational

- Encouraging shifts in behaviours and mindsets (doing and being)

If you’re keen to understand how stories are currently used by government and philanthropy, move to the next page.

If you want to skip to the barriers that get in the way of stories being listened to, proceed to the section about what gets in the way.

If you’re feeling action-oriented and are keen to dive into ideas and initiatives, jump ahead to read about what might be done to build he readiness of government and philanthropy to listen more deeply.

chapter 8: What we heard

The insights from this work are organised around three main questions:

How are stories currently used by government and philanthropy?

What gets in the way of stories being listened to and understood?

What might be done to build the readiness of government and philanthropy to listen more deeply?

chapter 9: How are stories currently used by government and philanthropy?

When we asked this question, we didn’t expect a simple answer. However, the range of uses identified far exceeded what we anticipated.

chapter 10: Stories are used to deepen understanding

We heard that stories can deepen understanding about the impact that policies and programs are having on people and communities. Robyn Scott, Executive Director of JR McKenzie Trust, explained that “stories reveal gaps and help us make sense of what’s needed and what’s working.”

We also heard from our group listening session that stories:

- “allow governments to hear and see the realities of their policies and practices from the ground up”

- “highlight the embodied reality of those impacted by policies and practice, rather than the idealised outcome”

- “capture the experiences, memories, questions, or concerns of groups in ways that are not able to be done via traditional research methods.”

Stories also deepen understanding by surfacing different perspectives. In their book Storylistening, Sarah Dillon and Claire Craig point out that “stories enable multiple points of view, increasing knowledge and understanding of a system.” They explain that this diversity of viewpoints “enables better understanding of both truths and untruths about a system.”

Others we spoke to pointed to the role of stories as a way of augmenting quantitative insights. As John King, former Executive Director of Analytics, Evaluation and Research at the Victorian Department of Health, explained that while data alone “gives you a thin sense of people’s complicated lives”, wrapping stories around that data “thickens it” and helps communicate the opportunities and impacts in ways that decision-makers can connect to. Colette Einfeld, Research Fellow at Crawford School of Public Policy, similarly shared how stories can be interwoven with statistical data to “give vibrancy and depth to the numbers.”

Finally, some felt that stories can highlight when policies and programs are working well and why. For example, Paul ‘t Hart, Professor of Public Administration at the Utrecht School of Governance, suggested that stories can help us celebrate when “the system is working as it should.” In contrast, others felt that we should focus on stories that help us understand failures or missteps. Donna Hall, Chair of New Local, suggested that it is “pointless listening to people who have had a good experience. Let’s listen to what went wrong.”

chapter 11: Stories are used to influence decision-makers

Many people highlighted that stories, particularly from people with lived experience, can inform the design of policies and programs. Tim Reddel, Professor at the Institute for Social Science Research at the University of Queensland, highlighted that stories and ethnography have an important role in shaping policy. Donna Hall, a strong proponent of ethnography in government, emphasised, “[government] needs to forge a new relationship with citizens centred around their stories.”

While she served as the Chief Executive of Wigan Council in the UK, Donna became interested in using people’s stories to shape public services. With her team, she trained every staff member – from frontline workers to the Executive Team – in ethnographic techniques. This taught staff to listen and engage with citizens differently, setting aside personal assumptions and taking the time to see the world through another’s perspective. As Donna explained, listening differently allowed staff to “be radical but humble public leaders who were able to embrace the reality of people’s lives and reshape our offer accordingly.”

While many agreed in theory about the importance of putting people’s stories at the centre of program and policy design, Deidre Mulkerin pointed out that this might require mindset shifts. She explained that “to privilege and honour lived experience means making space for it. It means turning down the volume on traditional tools and turning up the volume of lived experience.”

“Listening can be an act of transformative power provided it is done right.”

Ambelin Kwaymullina

chapter 12: Stories can offer new visions for the future

The idea that stories can be used to imagine and shape our future was a theme that emerged in our group listening sessions. One participant said, “We need stories to help us co-design what we want the future to be.”

This sentiment is echoed by Dillon and Craig’s book Storylistening: “Stories might not just describe the need for alternative models of the future, but provide them. Such stories might also be the product of collective imagining rather than of individual imagining.”

chapter 13: Using stories for ourselves

Several people we spoke to highlighted how stories are used for more internal purposes. This included stories being used in the following ways:

- To build trust and connection within teams. One senior civil servant pointed to a range of narrative techniques for team building. Similarly, in the group listening session, someone shared that “stories help the people I work with build connections and trust.”

- As a way of processing trauma. Paul ‘t Hart has seen storytelling used as a way of helping public servants process trauma. Sometimes, just telling stories can be an act of healing. As Meg Wheatley has said, “Listening is such a simple act. It requires us to be present, and that takes practice, but we don’t have to do anything else. We don’t have to advise, or coach, or sound wise. We just have to be willing to sit there and listen. If we can do that, we create moments in which real healing is available.”

- As a way of keeping people connected to the purpose of their work. Robyn Scott described stories as “keeping us feeling inspired and like we want to keep doing more of this work.” In the group listening session, we also heard that “stories keep those who are doing the work inspired, motivated, and connected.”

chapter 14: The shadow side of stories

It was clear from our conversations that stories are not always used as a force for good. We heard that stories can be used as a form of strategic mythology. For example, someone pointed to the infamous “Children Overboard” affair in Australia, where a particular story was told to drum up public support for stricter border controls. Cynthia Kurtz, author and Participatory Narrative Inquiry consultant, affirmed that stories can be used to “muddle and confuse people and trick them into believing things that aren’t true”.

Some people pointed to the danger of relying on a single story as a basis for decision-making. While the emotional nature of stories was identified as a strength, it can also create risks as single stories can capture people’s hearts and minds, leading to irrational decision-making. If a story doesn’t represent a larger pattern or trend, it shouldn’t be used as a basis for a big policy decision. In our conversation with Claire Craig, she stressed that in the context of social change, “it’s the collective impact of telling and listening that really matters.”

Others also pointed to the risks of simplifying stories to fit neatly into a public-facing document. To do this is to disrespect the storyholder’s agency and “tokenise” their story. This risks breaching trust, which can result in people not wanting to share their stories again, or even more significantly, risks compounding the trauma of storyholders.

This highlights that not all stories are worthy of our attention, and storylisteners need to be able to discern when this is the case. While not an easy task, it can be supported by focusing on collectives of stories rather than stories of individuals and using a mixed evidence base, which considers stories alongside other sources of evidence.

If you’re already feeling excited about this work and want to get involved in what comes next, jump straight to some more seedlings emerging.

If you’re keen to explore barriers and opportunities, keep reading.

chapter 15: What gets in the way of stories being listened to and understood?

In addition to understanding how those in government and philanthropy use stories, we also wanted to understand what gets in the way of stories being listened to and understood.

chapter 16: The perceived superiority of quantitative data

The strongest barrier that emerged through our listening sessions was the perceived superiority of quantitative data over stories. Numbers are perceived to offer a version of “the truth”, while stories are perceived to be “subjective”, “limited”, “jaundiced”, or even a “dark art”.

This acts as a real barrier to stories being listened to and understood. Frances Martin, Director of Service Development at Our Place, described being struck by “the perceived inferiority of stories as a source of information.” Similarly, Erica Potts, Director at the Department of Jobs, Skills, Industry and Regions, explained, “It is difficult for practitioners to find a place for a story because the pressure is to provide numbers.” We also heard in our group listening session that stories can be disregarded because they can “seem like marketing or fluff.”

There is a perception that while quantitative data offers a solid basis for decision-making, stories alone are insufficient. One public servant we spoke to suggested that “Politicians could safely make decisions just based on facts and figures; but not just based on stories.” Similarly, Bill Kermode offered that stories are helpful but “won’t go anywhere without sufficient evidence.”

Why is this the case? Erica Potts pointed to the “white coat” effect of data specialists. Erica explained that there is a perception that numbers don’t lie but was at pains to point out that, of course, they can:

“All the things people think about stories can also be true of data. There can be bias, inaccuracies, omissions… people should question data just as much as they question stories.”

Delving even more deeply into why numbers are seen as more “reliable and credible”, John King suggested that this bias is rooted in a Western worldview centred around scientific approaches and the logic of cause and effect. In their book Storylistening, Dillon and Craig elaborate on this:

“…the persuasive power of stories has contributed to their delegitimisation among the modes and models of rationality that have grounded Western democratic norms of evidence and public reasoning, norms consolidated in the Enlightenment, and rooted in rationalistic, positivist, and empiricist traditions.”

Robyn Scott’s work with Māori communities suggests that not all cultures prefer quantitative methods. Robyn explained how the communities she works with resist quantitative approaches because they tend to be used against them (as a weapon) far more than they’re used to support them.

chapter 17: Ensembles of evidence

Despite this apparent tension between scientific and narrative methods, Dillon and Craig argue that we should not see stories and quantitative data as opposing one another. Instead, we need to create ensembles of evidence. They explain,

“… What is needed is a pluralistic evidence base that combines the strengths of different forms of modelling and knowledge-generation.”

This was echoed by Erica Potts, who spoke about the “interweaving” of data and stories. Likewise, Tim Reddel asked, “How can we bring together storytelling and empirical work – not see them as dichotomies?” Nicola Hannigan and Suzie Warrick said,

“We talk about needing to shift hearts and minds. Stories are the heart. Data is the mind. And a combination of those leads to better decisions.”

The challenge with ensembles is that they can create tensions. We asked those we spoke to “what do you do if the quantitative data and stories paint different pictures?” For many, this tension is where the greatest insights emerge. As John King explained, “The tension that emerges is what forces the ‘why’ conversation, which is joyous. You have to embrace that tension and work through it with curiosity and humility, from multiple angles and sources.” This idea was reinforced by Dillon and Craig, who note that bringing together different forms of evidence creates greater uncertainty but makes “the future more visible and enable[s] those uncertainties to be engaged with more effectively.”

chapter 18: Additional barriers

Our listening sessions also surfaced a range of additional barriers that can get in the way of stories being heard, listened to, and understood. These include:

- Skills deficit: “People in government are not skilled, empowered, or expected to work with stories.” Erica Potts

- Power imbalances: “Governments, philanthropists, academics, and others who hold institutional power are in a position to decide which people are given the stage and which are not. They can decide whose stories are valid and whose are worthy of being heard.” Amy Denmeade, Ph.D. Scholar at the Crawford School of Public Policy

- An efficiency imperative: “In the drive for efficiency in the public service, we too often don’t invest enough time in storytelling” John King

- Unconscious bias: “People are cherry picking the stories that already fit with their narratives.” Daniel Daylight, Manager of Mt Druitt, Just Reinvest NSW

- Dominant narratives: “Stories occur in the context of other stories. The story of capitalism, for example, shapes how we understand other stories. We need to better articulate the assumptions underpinning our stories.” Amy Denmeade

- Narrative deficits: “Narrative deficits are areas in which there is a falling short either in terms of the ability or willingness to take stories seriously or because there is, in fact an (actual or perceived) absence of stories.” Sarah Dillon and Claire Craig

- Lack of relationships: “If you want to hear a good story, you need to build a good relationship. For people to share the history of who they are, it’s a very personal thing!” Turei Mackey, Strategic Communications at The Southern Initiative

- The desire for certainty and clarity: “We are required to have a neat answer. This doesn’t lend itself well to stories, which capture the variances and diversity that make up human nature.” Rachel Roberts

- A sense of professionalism: “People often assume you need to put walls up and have a professional distance. This gets in the way of genuinely hearing the stories of someone else. It’s not just the head; it’s the heart. This requires us to be vulnerable. And not everyone is comfortable with that.” Deidre Mulkerin

- Lack of connection between “story” people and “data” people: “It can feel like there is an oil and water effect between story people and data people. They often don’t collaborate well.” Erica Potts

In addition, one person we spoke to felt that there were few opportunities to speak to communities. They described feeling “blocked” from community, explaining that “fear, risk aversion, and a lack of good process to support the engagement” were the biggest barriers. However they did acknowledge that they knew of other governments who were “doing it much better than we are.”

We also heard from some that using stories in government is still not expected, while it is becoming the norm in the philanthropic sector. This sat in tension with the views of others who suggested that storytelling in government is now commonplace. For example, one senior public servant we spoke to suggested that most policy submissions she sees now include stories. She shared that as a leader in the public service, she’s constantly asking for stories from her team to illustrate the practical implications of a particular policy or service and observes others doing the same.

Finally, some people we spoke to highlighted that they are reluctant to ask for stories from community members in case nothing changes. Daniel Daylight explained, “What I’m protective of is seeing young people having to retell their trauma over and over again for things that don’t get results.” Similarly, Erica Potts pointed to her fear of “retraumatising people for a compelling story.”

One senior civil/ public servant stressed that if decision-makers listen to stories, they must be committed to making change:

“Our job is to work out how we can create opportunities for people to tell their stories and have them influence change. When people share their stories, we also need to have feedback mechanisms to let them know how we’ve used the information.”

In a similar vein, Frances Martin suggested that “honouring the story means feeling responsible for ensuring the story translates into change and action.”

While some people we spoke to suggested that failure to act on what is being heard will make people reluctant to share their stories again, Cynthia Kurtz offered a different perspective. She suggested that “if people feel disrespected and not heard, they will still tell stories. But they will tell different stories.”

If you haven’t read about how we captured the insights you just read about, jump back up to how we worked.

If you want to take a break from reading our insights and want to read the work and thinking of others, jump to resources.

Read on if you want to learn more about what might be done to support better listening.

chapter 19: What might be done to build the readiness of government and philanthropy to listen more deeply?

For our final element of this phase of work, we wanted to move from insight to action. We wanted to understand what might be done to build the readiness of government and philanthropy to hear, listen to, and understand stories. Below, we share some of what we heard.

For each initiative, we offer examples of what this might look like in practice, drawing on ideas and inspiration from around the world.

Given this section is about moving to action, we encourage you to read it in that spirit. Explore the themes below, pick those that resonate most, and think about how you might be able to use them in your context.

chapter 20: Build storylistening skills

Invest in ethnographic skills.

- The work of Donna Hall and Robin Pharoah in Wigan shows how one Local Council trained staff in ethnographic techniques.

- PolicyLab in the UK has used ethnographic approaches to improve policymaking.

Develop the storylistening skills of decision-makers.

- Digital Storytellers supports local government to develop skills in telling and listening to stories.

- Yarn Australia’s courses focus on storytelling and storylistening.

- What Matters To You is designed to support healthcare professionals in deep listening.

Explicitly recruit for narrative skills.

- Cities are recruiting Chief Storytellers, and some are focusing on listening.

- Burnie Works recruits local Community Knowledge Collectors who are skilled and supported to collect stories.

chapter 21: Invest in relationships

Create a culture which values building relationships with storyholders.

- The Southern Initiative focuses on building relationships first and gathering stories once trust is established.

Bring government, philanthropy, and storytellers together to have brave conversations.

- Our Place has shared their experience building relationships between government, philanthropy, and community.

- Community Conversations are commonly used to bring people from different sectors together to have generative conversations.

Embrace a relational approach to funding and grant-making.

- Relational approaches to funding are central to the work of the JR McKenzie Trust and other philanthropic organisations.

- Commissioning in Complexity offers insights into a relational approach to funding in government.

Consider whether payment for stories feels appropriate.

- Cynthia Kurtz suggested that when people are paid, stories become commodified and performative. Others have written about the importance of remuneration.

chapter 22: Invest in co-design skills

- K A McKercher’s book “Beyond Sticky Notes: Codesign for Real” aims to help individuals and teams co-design better.

- Emma Blomkamp offers courses and coaching on co-design.

chapter 23: Create dedicated storytelling or storylistening spaces

- Mounty Yarns is a youth-led project presented as stories, expertise, and knowledge by and with Aboriginal young people with lived experience of the criminal justice system.

- Digital Stories Canada suggests creating and holding safe spaces for stories to emerge.

chapter 24: Bring together data and story people

Train people in ensemble thinking.

- Dartington Service Design Lab has explored integrated approaches to evidence.

- Better Evaluation includes resources on mixed methods approaches.

Draw on the expertise of organisations blending data and story in ways that acknowledge complexity.

- Seer Data and Analytics empowers data-led decision-making for communities, while Kowa amplifies the voices of First Nations peoples in impact measurement, evaluation, and learning.

Utilise technology-based tools which blend stories and data.

- SenseMaker® is a distributed ethnographic tool that empowers community members to tell and interpret their story and gather material.

chapter 25: Some more seedlings emerging

This second branch of work, like the first, has revealed new insights, raised new questions, and offered a range of possibilities and ideas for how we might grow new branches and strengthen those that are already established.

Like last time, we approached this work with the intention of generating value beyond the report. We know that the conversations we’ve had over the past several months have already generated new ideas and opportunities, and we are keen to continue these and see what emerges.

If you would like to be part of a community of people interested in exploring this work further, join our Storytelling Community of Practice.

If you work in philanthropy or government and are keen to explore these ideas in more detail, we’d love to hear from you.

“Long before I wrote stories, I listened for stories. Listening for them is something more acute than listening to them”

Eudora Welty

Resources

- Everything is copy: why storytelling matters, for philanthropy and otherwise - Alexandra Hudson

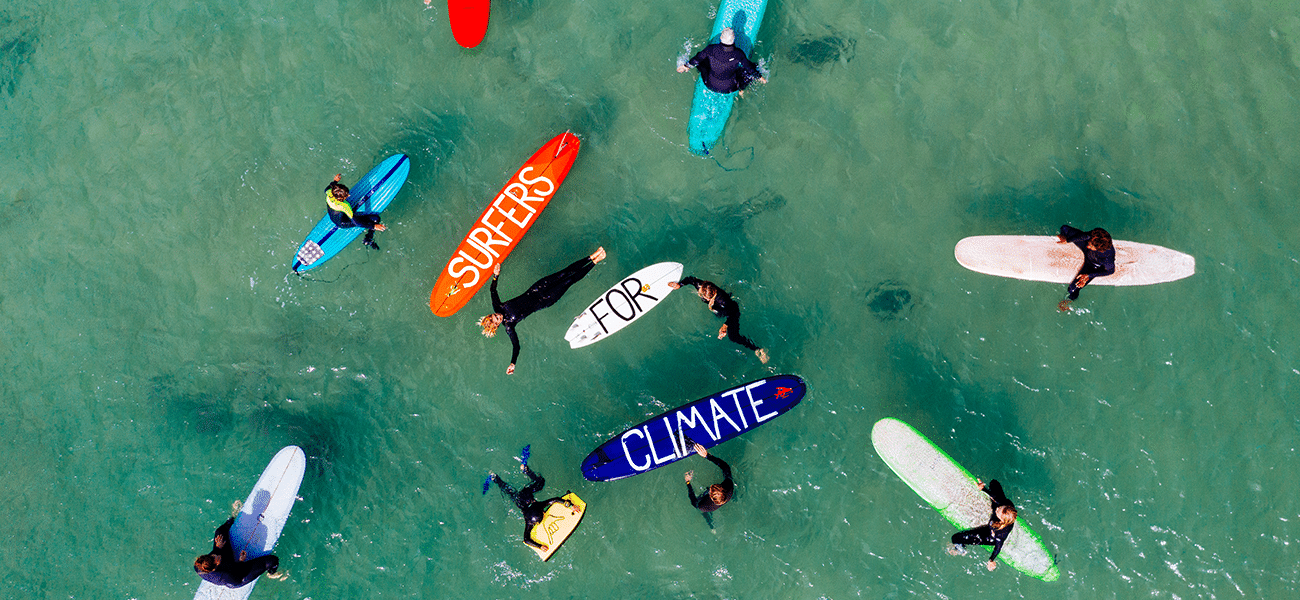

- The Power of Climate Storytelling - Anna Jane Joyner, Paddy Loughman, Will Travis, Samuel Rubin

- How to Tell Real Stories About Impact - Annie Neiymand

- Why policy narrative matters: Effective government responses to COVID-19 - ANZSOG

- Stories from the Community - Australian Communities Foundation

- Growing Up the Future: Children’s Stories and Aboriginal Ecology - Blaze Kwaymullina et al

- Rigorous Evaluation Versus Trust-Based Learning: Is This a Valid Dichotomy? - Brenda Solorzano, Headwaters Foundation

- Stories Beat Statistics: Master the Art & Science of Data Storytelling (video) - Brent Dykes

- Storytelling and evidence-based policy: Lessons from the grey literature - Brett Davidson

- Sheep Farming After Chernobyl: a case study in communicating scientific information - Brian Wynne

- Effective Listening: The Secret To Powerful Communications With Dr. Kittie Watson (audio) - Business Confidential Now Podcast

- Thomas Mayo: Voice to Parliament (audio) - Changemakers Podcast

- Storylistening: Narrative evidence and Public Reasoning - Claire Craig and Sarah Dillon

- About Participatory Narrative Inquiry - Cynthia Kurtz

- Retelling the story of humans and nature (video) - Damon Gameau, TEDx Talk

- Narrative Patterns: The Perils and Possibilities of Using Story in Organizations - David J Snowden

- Narratives as tools for influencing policy change Desrai Crow and Michael Joesl

- System change using storytelling - Digital Storytellers

- Stories for Impact - Digital Storytellers blog series

- Introducing Internarratives - Ella Saltmarshe

- Team Up Use Folktale to Increase Shared Understanding - Folktale

- Public Policy as Narrative - Frank Fischer

- Towards more proximate storytelling in philanthropy - Gabriel Diamond, Skoll Foundation

- A New Framework for Understanding Power Building - Gigi Barsoum

- Conversations about Working with Stories and Storytelling with Cynthia Kurtz (video) - GloComNet Conversation Series

- Behavioural Insight Brief: The Role of Narrative in Public Policy - Government of Canada

- Make the Move - Inspiring Communities

- The International Resource for Impact and Storytelling - IRIS

- Empathic Listening: The Highest Form of Listening - J.D Meier

- Storytelling for social change - Jemimah McMurray, Australian Philanthropic Services

- Listening is a Form of Healing - Jennifer Brandel

- Finding Climate Solutions in Fairy Tales - Katherine Ellsworth-Kerbs & Becky Tipper

- Listening as Healing - Margaret Wheatley

- Mastering the art of the narrative: using stories to shape public policy - Michael D Jones and Deserai Crow

- Mounty Yarns - Mt Druitt Youth, Just Reinvest NSW

- Making Open – Design Kit & Workshops - Nook Studios

- Cynefin.io - Open Source

- How are you listening as a leader? - Otto Scharmer

- The Four Levels of Listening (video) - Otto Scharmer

- The State of Storytelling in Philanthropy - R.J Bee

- Telling the Story of your Project. Using the Tiger Who Came to Tea - Sam Villis

- Power of changing narratives for system change - Stephanie Draper

- Lean Story Canvas - Stronger Stories

- Nathaniel Rich on Storytelling and the Climate Crisis (audio) - Talk Easy Podcast

- Explode on Impact - Toby Lowe

- Ambelin Kwaymullina on the importance of truth listening (audio) - Victoria With David Astle, ABC Radio Melbourne

- On Polarization (video) - Yuval Noah Harari and Esther Perel in Conversation

Digests

The following are an archive of the Digests we shared along the way to provide regular updates to everyone who gave their time to the listening sessions.

Further acknowledgements

We want to thank Imogen Baker for her work in magically weaving together people’s voices to create the audio pieces you will find throughout the report. Thank you also to Kirsten Moergelein who has brought these voices to life with her beautiful artwork.

A big thank you to Rosie McIntosh and Carmella Grace De Guzman from the Centre for Public Impact who have played an integral role in shaping this report and helping us share it with the world.

We also want to thank those who gave up their time to speak to us and share their stories. A big thank you to:

- Alison Frame – Department of Veterans’ Affairs

- Amber Swaby – Black Thrive

- Amy Denmeade – Crawford School of Public Policy

- Bill Kermode – Next Foundation

- Claire Craig – Author of Storylistening

- Colette Einfeld – Crawford School of Public Policy

- Cynthia Kurtz – Participatory Narrative Inquiry Consulting

- Daniel Daylight – Just Reinvest NSW

- Dave Snowden – The Cynefin Co

- Deidre Mulkerin – Department of Child Safety, Seniors and Disability Services

- Donna Hall – New Local

- Doug Cronin – Our Race

- Erica Potts – Department of Jobs, Skills, Industry and Regions

- Evonne Miller – Queensland University of Technology Design Lab

- Frances Martin – Our Place

- Ibrahim El Badawi – 01Gov

- John King – Department of Health

- Josh Schachter – CommunityShare and Creative Narrations

- Josue Aruna – Environmental and Agro-Rural Civil Society

- Lyndal Carberry – Northern Territory Health

- Maria Höyssä – Committee for the Future

- Michael Appouh – Black Thrive

- Nicola Hannigan – Paul Ramsay Foundation

- Nour Sidawi – Ministry of Justice

- Noureen Vadsaria – Black Thrive

- Paul ‘t Hart – School of Public Administration

- Rachel Roberts – Inspiring Communities

- Robert Slape – Transport Canberra and City Services

- Robyn Scott – JR McKenzie Trust

- Rosie McIntosh – Centre for Public Impact

- Shandel Pile – Burnie Community House

- Susan Johnston – Natural Resources Canada

- Suzie Warrick – Paul Ramsay Foundation

- Tim Reddel – Institute for Social Science Research

- Turei Mackey – The Southern Initiative