Report

Storytelling for Systems Change: Insights from the Field

Thea Snow and David Murikumthara (Centre for Public Impact)Teya Dusseldorp and Rachel Fyfe (Dusseldorp Forum) Lila Wolff and Jane McCracken (Hands Up Mallee)

“Storytelling reveals meaning without committing the error of defining it.”

Hannah Arendt

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which this project was created, and pay our respects to their Elders past and present. We also acknowledge their ancient connection with storytelling and how it shapes our world and our connections to it.

Our Storytelling for Systems Change work would not be what it is without the contributions of many. See the names of everyone who contributed.

chapter 1: Executive summary

This is a story about a group of three organisations who wanted to better understand the role of storytelling in place-based, community-led work. These three organisations – Dusseldorp Forum, Hands Up Mallee and the Centre for Public Impact – didn’t know each other very well, so it’s also a story about new partnerships, and exploring new ways of working together.

This is a story of unexpected and delightful discovery. Our journey began with a question around how stories could be used to more effectively communicate the impact of community-led systems change work to decision-makers in government. But our conversations opened up new pathways of inquiry and led us to places we didn’t expect to go, broadening the scope of our findings well beyond the project’s original framing.

We learned through this process that stories can be used to change the system, as well as to evaluate, understand and showcase the change that is occurring in communities. We have heard that different stories require different approaches – stories that are seeking to enable change look different to those that are seeking to celebrate change.

We have learned that great stories privilege the voice of the story-holder; are resonant, clear and relatable; and are guided and bound by agreed protocols. However, we have also heard that technical, structural and institutional barriers can get in the way of good storytelling.

Finally, this project has revealed a deep passion and enthusiasm for storytelling across a broad spectrum of actors. It created a space for people to share ideas and possibilities about what stories can and should be, as well as the kinds of infrastructure, investment and explorations that might be needed to support stories to be both told and heard.

This isn’t our story – it’s the story of the backbone teams, community members, organisations and storytellers we spoke to. It’s also a story for backbone teams and community members, as well as for philanthropists, organisations and government teams working to support and enable initiatives for place-based systems change.

This is not the end of the story; in fact, it’s just the beginning. As we close this chapter, which has focused on understanding the role of storytelling, we are already beginning to think about what the next chapter might look like. If you’re interested in exploring how storytelling can be used to both enable and celebrate community led systems change work, and would like to become a co-author in the next stage of our story, we’d love to hear from you.

chapter 2: The story of the storytelling project

This story began with an observation. Or perhaps it began before then. We’re not sure. It’s hard to know, really, where stories begin.

The observation was made by Teya Dusseldorp, who shared something that had been on her mind – “I work with communities who are engaged in such inspiring systems change work. Yet so few of their stories are being heard. I want to understand why, and support them to tell their stories more effectively.”

It was this enquiry that catalysed this story – the story of a partnership between the Dusseldorp Forum, Hands Up Mallee and the Centre for Public Impact, designed to deepen our understanding of what might be needed to equip those engaging in systemic change agendas to develop stronger capabilities in crafting and telling their own stories.

The seeds of this story were, without question, sown long before this chapter began. Dusseldorp Forum has been working alongside communities who are engaged in the hard work of systems change over many years. Community-led, place-based initiatives are modelling new ways of working – shifting away from top-down, program-focused approaches towards an approach grounded in systems thinking and community-led innovations. These new ways of working are having a profound impact on communities in different parts of Australia. Across the country, we’re seeing communities and police working together in new ways in Bourke; new models of maternity and child healthcare in Logan designed with community, for community; collaborative breakfast partnerships across kindergartens and schools leading to emotional, academic and health benefits for children in Mallee; and much more.

However, Dusseldorp Forum has been struck by the fact that while compelling stories of positive systems change are sitting in communities, they’re often not being shared or celebrated – and certainly not in a concerted and coordinated way. But why? And what might be done to address this?

Part of Dusseldorp Forum’s story to date has been about revealing and grappling with this question.

And it is from their story, and these questions, that this story grew – the story of Dusseldorp Forum, Hands Up Mallee and the Centre for Public Impact setting out to explore what good storytelling looks like; what the barriers to storytelling might be; how stories can support systems change; and what practical tools, training and processes might be needed to better enable those involved in community-led systems change initiatives to tell compelling stories about the nature and impact of their work – and have those stories heard.

What do we mean by systems change?

There are many definitions of “systems change” available but, for the purposes of this work, we’re adopting the definition offered in NPC’s report Systems change: a guide to what it is and how to do it:

“Systems change aims to bring about lasting change by altering underlying structures and supporting mechanisms which make the system operate in a particular way. These can include policies, routines, relationships, resources, power structures and values.”

This is a story that, from seeds sown years ago, has grown many new and still relatively immature branches. Some of these branches are rooted in what we have learnt about how to work as a team, others in the insights that have emerged from our conversations with all the people listed in the Acknowledgements section.

The rest of this story will explore these branches.

chapter 3: Standing on the shoulders of giants

Before we begin sharing the insights from our story, we want to spend a brief moment acknowledging the thinking and knowledge that has shaped this work.

The fields of storytelling, narrative shift, and systems change all have vast literatures, expertise and wisdom associated with them. There is certainly a huge amount to be learnt from this rich and pre-existing knowledge base. However, we decided as a project team to quite deliberately generate insights from conversations with community and storytellers, rather than focusing too heavily on existing theory and literature. We did this for a range of reasons and certainly, in part, because as John Le Carr. has pointed out, “a desk is a dangerous place from which to view the world.”

That said, this project has also been shaped by the thinking of many deep experts in this field, and it feels important to acknowledge this.

Some of the key thinking and literature we have drawn on includes:

- The wisdom and insights of Australia’s First Nations peoples – the original system thinkers and storytellers – who have highlighted the importance of deep listening, non-egotistical stories, and using stories as a way of shifting the conditions that hold systems in place.

- Frameworks Institute, whose work highlights how to use stories and narrative shift to drive social change.

- The Narrative Initiative, whose waves model has shaped our understanding of the relationship between values, narrative and stories.

- Ella Saltmarsh’s article, Using Story to Change Systems, which explores how story and narrative can be used to change systems.

- Donella Meadows’ work on leverage points, FSG’s Water of Systems Change Report, and the System Sanctuary’s adaptation of Geels’ Transition Theory, all of which have shaped our understanding of how to encourage and enable systems change.

- The Passing the Message Stick Report, which highlights the importance of rejecting deficit narratives in favour of narratives centred on strength and capability.

A more comprehensive list of relevant resources and articles is included at Resources.

chapter 4: How we worked

The first branch of this story relates to how we worked – both as a project team and with the people we listened to and worked with along the way. The project team began by developing a Team Charter to guide how we would work together, and with others.

Team Charter:

As a team we value trust and coordination as a team. In practice, this means we:

- hold regular check-ins to discuss the project, and provide feedback as a group (currently set to be weekly);

- share insights from interviews and separate conversations;

- commit to honesty and openness as a team, both internally and externally;

- act with compassion and empathy for each other and those we engage with in the project;

- update the team where there are deviations to deliverables/timelines.

As a team we value feedback, evaluation and improvement. In practice, this means we:

- let each other know if something isn’t working as we hoped it would;

- discuss what went well, what could go better in regular check-ins, including feedback from interviews (what went well, what didn’t) to refine further interviews;

- provide a feedback loop for those who contribute as part of the project – we let interviewees provide feedback on imagination sessions, interviews, and the final report.

As a team we value diversity, equity and inclusion. In practice, this means we:

- include diverse perspectives in all processes (including listening and imagining sessions);

- include and centre indigenous approaches to storytelling;

- use community language that is understood by all;

- provide space to not reach consensus on all things, and the ability to hold diverse opinions;

- conduct work in settings and times that work for the access needs of participants.

As a team we value collaboration and empowerment. In practice, this means we:

- conduct interactions in a way that is empowering for people and communities – the way we work is as important as the final product;

- always keep in mind that collaboration with communities is at the heart of the work;

- are mindful in all we do to build confidence and capacity – the interviews themselves should build capacity;

- leave people feeling good about themselves after listening and imagination sessions;

- make sure that the imagination session and report reflects what we heard;

- have an open source final report that is available to all;

- Do not ask of community things that are too onerous.

chapter 5: What does success look and feel like based on agreed project objectives?

We also defined upfront what success would look and feel like for this project…

-

A report that is action oriented

-

A report that might be presented in multi-media ways / not just written and is accessible

-

Backbones are engaged in processing storytelling in their communities

-

Community involved every step of the way

-

A final product that sparks discussion and widely shared

-

Ah ha moments

-

People feel that sharing stories has value (as much if not more than formal evaluation/reports)

-

Fun

-

Exciting and motivating

-

We all look forward to our weekly check-ins

-

People motivated to take on phase 2 together

-

We are learning valuable things as we go

-

Communities feel like they have important stories to tell

-

People think that story telling is important and prioritize it – mindset shift

chapter 6: Things we want to avoid

As well as things we wanted to avoid, which included…

- A theoretical report that gathers dust in the bowels of the internet

- Wasting people’s time

- Setting impossible goals for communities

- An un-inspiring recipe book

- A report that doesn’t progress the objective of increasing effective story telling

- Something or about people who don’t look like how they want to be acknowledged in stories

- All knowledge is wrapped up in the report

- People feeling their input was not used/really heard

To stay true to the principles set out in the Charter, we realised that it was our role to listen, rather than to try to find or offer answers ourselves. To achieve this, we brought together collective impact backbone teams, community members pursuing a community-led approach to change, storytelling experts, and those working in and around community-led systems change initiatives for a series of listening sessions. These were designed to help the project team better understand the challenges and opportunities around storytelling from these different perspectives. The questions we used to guide these listening sessions are included in conversation guide for listening sessions.

As our framing of “what success looks like” highlights, we wanted the impact of this project to be diffused. We wanted to ensure that the key insights and “ah-ha” moments weren’t all wrapped up in the final report, but could emerge organically through the conversations we were having, creating immediate value and insight for those who had generously agreed to participate in this process. For this reason, how we worked together was a very important part of this project.

The project team met weekly for 30 minutes throughout the project to connect, share and progress actions as a team.

To ensure we were sharing what we were learning along the way, we developed a weekly Storytelling Digest that we emailed to those who gave their time to the listening sessions (see Storytelling Digests). We also wrote blogs along the way, to enable those more broadly interested in the topic to learn about what we were doing.

Once we had gathered all the key insights from the listening sessions, we asked everyone who had participated in a listening session to a sensemaking and imagination workshop. Here, we invited them to help us make sense of what we’d heard through our conversation, exploring emerging patterns and connections as well as what might be possible if there were no constraints.

And finally, in writing this report, rather than wait until it felt perfect, we shared an early draft with everyone who had attended the listening sessions or sensemaking workshops. People commented, made suggestions, and highlighted points they felt we’d missed. We have no doubt that this work is better as a result.

So, an important branch of this story is not just what we discovered, but how we went about discovering it. We attempted to create an approach which was open – sharing our learning, our mistakes, as well as the insights emerging from the project along the way. We also tried to invoke a spirit of collaboration and humility, recognising that the best role for us to play was to give others a space where they could tell their stories.

chapter 7: What we heard

The second branch of this story relates to what we heard through our listening and sensemaking work. This branch was organised around three main questions:

- Is storytelling important in driving systems change

- What does good storytelling look like?

- What makes it hard to tell stories about systems change work?

Below, we set out the ideas, themes and questions that emerged from our conversations.

chapter 8: Is storytelling important in driving systems change?

The short answer that people offered to this question was “yes”. But precisely how stories create change was where the interesting insights emerged.

As Sam Rye explained, stories play different roles at different levels of the system – stories both “support systems to change, and also shine a light on the change”. In other words, stories can be used to change the system; as well to evaluate, understand and showcase the change that is occurring.

Circling back to our definition of systems change (above), we can see that one way for stories to change the system is by supporting individuals to change how they see themselves, their communities, and their broader context. Systems change when people change how they relate to others, who they are in relationship with, and what they believe they are capable of doing.

We heard that stories change the system by supporting individuals to:

- Build empathy with other perspectives – “stories are empathy machines.” Dalit Kaplan, Storywell

- Shift their mindsets – “storytelling is about shifting mindsets and perceptions.” Alistair Ferguson, Maranguka

- Heal – “we’re actually talking about creating transformational spaces. Storytelling is just a tool. This is sacred work… we’re talking about healing for transformation. If people are transformed through the process of sharing stories, workers are transformed, systems are transformed.” Kylie Burgess, Burnie Works

- Build new connections, relationships and conversations – “storytelling is a really great tool for empowering others. It is that mutual playing field where we all have a story to tell and share, with which it then creates that relationship. And we all know that being connected and having strong relationships is a necessary foundation for all of us.” Shandel Pile, Burnie Community House

- Teach and learn – “you can’t unlearn someone else’s perspective once you’ve experienced it through a story.” Dalit Kaplan, Storywell

- See new possibilities – “seeing other people’s stories opens up the possibilities of what you can be… People need to be able to tell their story to change their story.” Bre Macfarlane from Home Base, Mildura

- Understand and see the world in different ways – “stories construct our reality.” Amy Denmeade, PhD candidate at the Crawford School of Public Policy

Two of the First Nations Peoples we spoke with as part of this work, Rona Glynn-McDonald from Common Ground and Tyson Yunkaporta from Deakin University, both highlighted the role that stories can play in reshaping the rules of the systems – what Rona called “governance and protocols.” Tyson explained that “story has a role to play in governance models and connecting everybody up through common law/lore.”

In addition to changing the system, stories also help to shine a light on the way things are shifting within communities. Stories can act as evidence of the change, for example, through the Most Significant Change technique. As Kerry Graham of Collaboration for Impact highlighted, “people are hungry for vignettes of change – to see someone else has done it and it’s worked. Stories do this well.”

A number of people we spoke to also highlighted that, in order to be most effective, different storytelling approaches are needed for the different types of stories described above. Simon Goff, from Purpose, explained that what good storytelling looks like depends on what you want to achieve – internal truth-telling, hashtag, and advocacy campaigns all require vastly different tools and approaches.

What this reveals:

- Stories change the system as well as illuminating the changes that are taking place.

- Different forms of storytelling are needed depending on what you are hoping to achieve by creating and sharing the story.

What this makes us wonder:

- What barriers get in the way of using stories as evidence of change, and how might these barriers be addressed?

- Should we always be ensuring that stories meet audiences where they’re comfortable, or is it OK to use stories as a means of stretching audiences out of their comfort zone?

- Are we making assumptions around what effective storytelling looks like? Could we be more experimental with this?

chapter 9: What does good storytelling look like?

A strong theme that emerged was that good stories must be authentic, and must honour the voice of the person whose story is being told. Many people we spoke to highlighted the importance of stories being told using the language and voice of the community.

As Skye Trudgett from the National Centre for Indigenous Excellence (who also works as the data manager for the Maranguka team) said to us, “I think this is where we need to move away from preferencing institutional data. Not the numbers, how do we actually push the community voice up because that is more powerful than… numbers.”

In addition, it should be story-holders who decide which stories should be told, and how they should be told. Unlike data, which is often defined, harvested and interpreted with very little community involvement, storytelling offers an opportunity for much greater agency and control by the storyholders. As Nikita Hart, Community Liaison Officer for Connected Beginnings explained, “data takes away people’s ownership of their story; storytelling gives that power back to them”. A number of people also highlighted the importance of respecting data sovereignty – for Rona Glynn-McDonald, data sovereignty in the context of storytelling means being very conscious of “how we tell stories, who owns them, and who tells them”.

However, while there was strong agreement that centring community voice and control is key, it was also highlighted by many that this is uncommon. In addition, it can feel challenging to use stories for the purpose of advocacy, while also honouring the person whose story it is. As Catherine Thompson from Hands Up Mallee explained, “it’s hard to take a story, not lose the voice behind it, but also shape it so that it has influence”.

Our conversations revealed that good stories resist bending themselves to fit a pre-existing narrative – they tell the story that needs to be told, even if that sits somewhat in tension with the dominant narrative. This is critical, because telling stories that challenge the dominant narrative actually helps to dislodge that narrative. As the Passing the Message Stick Report highlights:

“The words we use matter. When we share our vision and truth, we can build powerful movements and win public policy and transformative changes we’ve been calling for… When we repeat effective messages we can shift public support and win transformative change.”

Conversations also highlighted that good stories are resonant, warm and relatable. Good stories:

- don’t use academic language

- are persuasive and engaging

- are emotional – they capture the heart

- go deeper than data – providing more context and insight than numbers can

- are honest, authentic, inclusive and gentle.

Good stories are also accessible. Kerry Graham noted that “of the comms pieces I’ve seen, the good ones are short and consumable in one sitting”.

It was also pointed out that not all stories are good stories. Tyson Yunkaporta suggested that good stories are “signal” – they are not driven by any agenda or claim for dominance. This can be contrasted with stories as “noise” – stories shaped to serve someone’s agenda and to elevate their needs above others. Others highlighted that stories are not good when they:

- pass judgment on a person’s situation

- are centred in ego

- are designed to promote something

- are driven by the motives of the storyteller, rather than the needs and priorities of the community.

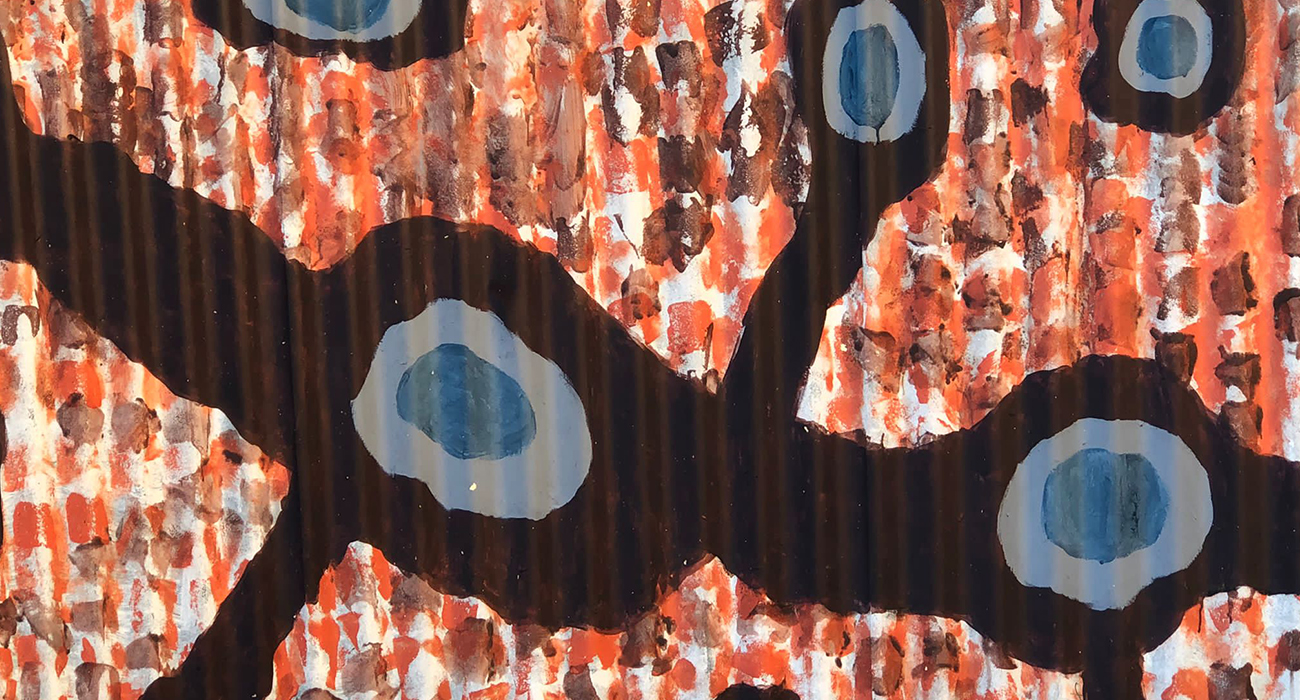

We also heard that stories can take many forms – from the more mechanistic case studies and testimonials to immersive experiences, like those which Sarah Barns from Storybox creates. Sarah pointed out that there are already many practices and disciplines that have storytelling with impact at their heart – from film and documentary to podcasts to theatre and more. Echoing the expansive nature of storytelling, Rona Glynn-McDonald explained that stories can be “songlines, dreaming, law/lore, protocol, and a living archive.”

Another idea which emerged was that stories of systems change need to embrace nonlinear, dynamic and more fluid forms. As Abigail Graham from the Latrobe Valley Authority explained, stories about systems change work require different layers – they are like “Russian dolls in terms of nested layers and interconnected loops”. Bre Macfarlane from Home Base, Mildura also highlighted the importance of being able to “keep building on the story as it grows and changes”.

The final theme was that good stories need to be guided and bound by protocols. These protocols can cover obvious things, like ensuring there are clear rules around how stories can be used, that story-holders are given the chance to review stories before they are shared, and that stories are accurate. However, protocols can also offer guidance on more subtle issues, like ensuring stories preserve dignity, agency and nuance. We heard about the importance of having processes and practices in place which make the people sharing their stories feel safe, protected and respected. We also learned that First Nations Peoples in Australia have dedicated owners and managers of stories.

What this reveals:

- To be effective, stories of systems change should: privilege the voice of the story-holder; be resonant, clear and relatable; embrace a nonlinear, layered and fluid form; and be guided and bound by agreed protocols

- Stories of systems change can take many different forms.

What this makes us wonder:

- Is it ever OK to compromise on a story’s authenticity if it is felt that making that compromise means the story is likely to achieve a greater impact (because, for example, it is told in a way which resonates with a productivity and measurement-oriented government minister)?

- Nonlinear stories are unfamiliar and can be challenging! Can we really expect them to resonate when we’ve been so conditioned to something quite different?

- How can we balance the need for stories to be accessible and “consumable in one sitting” with the need for stories to be layered and complex?

- What might we learn from the First Peoples’ tradition of having story owners and managers?

chapter 10: What makes it hard to tell stories about systems change work?

When we asked people to consider what makes it hard to tell stories about systems change work, six key themes emerged:

Power and trust: Power imbalances and a lack of trust can make it very hard for people to share their stories. Sharing stories requires rawness and vulnerability, which will only happen if people feel safe and believe that there is value in sharing their stories. But often insufficient time is dedicated to building trust and respect between those sharing their stories and those capturing them.

The complex nature of the work being described: Systems change is messy work – it involves so many parts of the system working together to drive change, and that can be very hard to capture in a story. As Kerry Graham explained, “we’re trained to respond to linear stories where there’s a problem > action > solution. These stories don’t fit that formula.” This can be a challenge, both because it makes the story more difficult to craft and because governments and philanthropists – who are essential funders of community-led, place-based work – tend to look for neat stories of cause and effect, which these stories are not.

Skills, resources and capability: A key barrier to effective storytelling is simply not having the time or funding to do it well. It is time- and resource-intensive to capture and share stories and, as Nicole Mekler from Maranguka explained, “stories get lost in doing the work”. In addition to a lack of capacity, a lack of capability around storytelling was also highlighted as a challenge. As Melanie Corona from Burnie Works pointed out, storytelling does not come naturally to everyone. With this in mind, Dalit Kaplan suggested that it is important to invest in people’s “story literacy”, which involves building their understanding of the “science” of story architecture, as well as the “art” of a compelling story.

Readiness to receive stories: Another challenge highlighted was that to have an impact, stories need to be heard. For stories to effect change, the right people need to not only listen to the stories, but also hear them. As Fiona Merlin from the HUM Backbone team explained, there’s a difference between listening to a story and hearing it – we need an audience who “listen to understand”. But this is easier said than done. Sometimes listeners aren’t ready to receive the message. Sometimes the timing just isn’t right for the message to land in a way which actually brings about the change needed. Sometimes it’s hard to get stories to the ears, eyes and hearts of people who most need to hear them. Fiona summed this up with a powerful question – “how can we tell stories in ways which encourage the listener to not just hear, but actually connect to a different view?”

The limitations of language: Finding the right language to tell the stories of systems change was also seen to be a significant challenge. As Rowena Cann from the Latrobe Valley Authority highlighted, stories of systems change are about changes in mindsets, practices and capabilities, and these are not the kind of stories government officials are used to hearing. The tendency to use deficit-oriented language was also called out, not necessarily as something which makes it hard to tell stories per se, but as something which makes it hard to use stories to drive systems change. Rona Glynn-McDonald asked, “if we’ve been telling stories based on colonial lenses, deficit mindsets, how can we expect to create new systems?”

Bias: Storytelling is not a neutral exercise. The way that questions are framed, the way that answers are interpreted, what is left out and what is included, all act to shape the stories that emerge. Even as the project team, we make choices about who we’re interviewing, what we’re asking, and what we’re including in this final report. In this way, the project team is shaping the story of our storytelling project.

What this reveals:

- The factors that make storytelling hard are technical, structural and institutional. The technical barriers – such as lack of skills, resources and capability – are easier to address than the structural and institutional barriers, such as power imbalances and bias.

- In order for stories to contribute to systems change, energy needs to be spent on both the supply and the demand sides of the equation. In other words, we need to understand both how to support people to tell better stories and how to increase the likelihood that there is an audience ready and willing to hear and respond to the stories.

What this makes us wonder:

- Most of the effort around storytelling focuses on the supply side – how might we start thinking about practical ways to address the demand side of the equation?

- How can we honour the complexity of the work taking place in communities, while also crafting stories that people can understand and feel inspired by?

chapter 11: Vision and opportunities

The third and final branch of the story is rooted in imagination. Building on the insights that emerged from the sensemaking process, participants were invited to think creatively and audaciously about how they could see storytelling playing an impactful role in supporting systems change work.

We encouraged people to use their imagination (rather than their rational mind, constrained by budgets, norms and existing structures), to explore what stories for systems change might look like, how they might be used to support systems change, and what type of supporting infrastructure might be needed.

chapter 12: What might stories look like?

People highlighted that stories can be art as well as immersive and embodied experiences.

- Chains on fences

- Plaques in Elwood canal

- Dioramas – community artefacts and stories<

- Songs

- Sculpture as symbolic story telling as in today’s press

The power of immersive storytelling was emphasised by Kerry Graham, who pointed out that, “I’ve only really seen people’s mental models shift when they are immersed in the work/ the place/ the feeling… how do you create moments of that?”

- Story through food

- Shinrin yoku forest therapy – communicating with nature e.g. conservations and listening to trees, reducing stress etc.

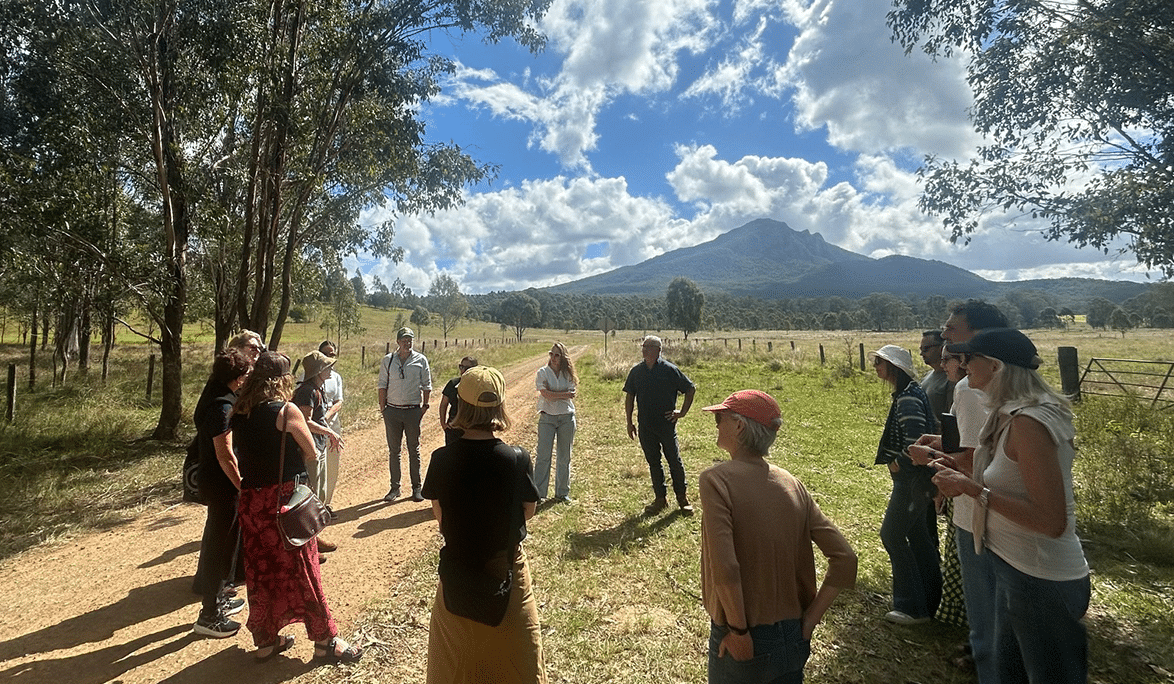

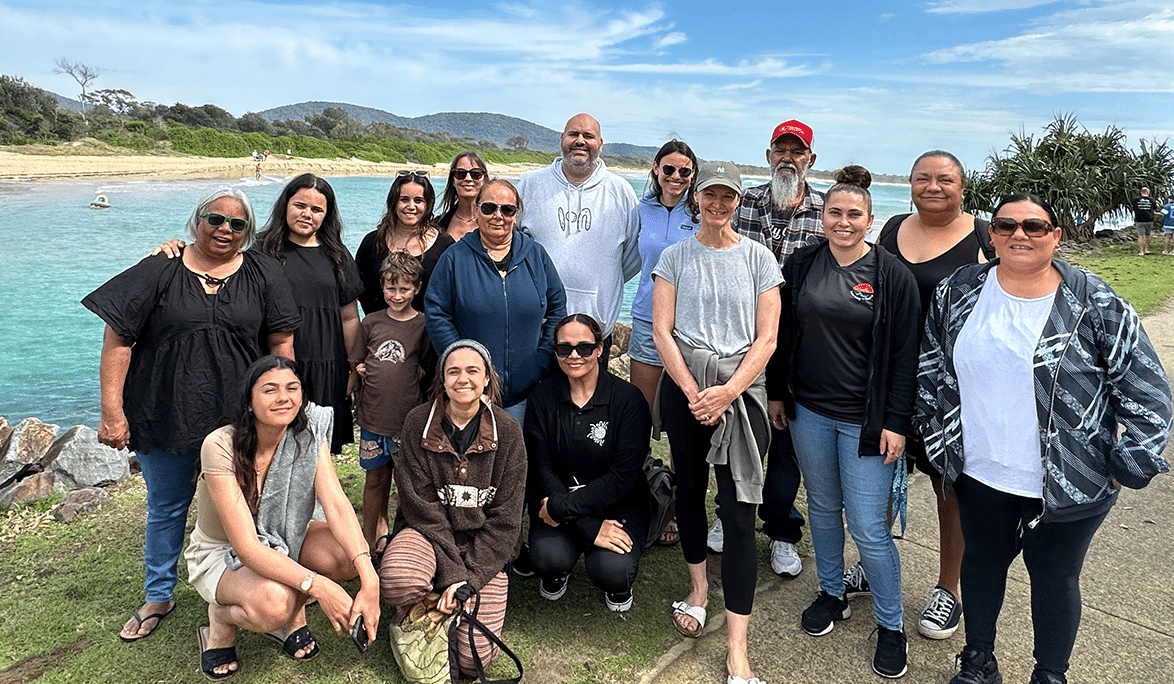

- On Country – more getting out into nature with groups to inspire new perspectives for stories (a way to view a narrative differently)

- Stories <> Ceremony

- Stories as ritual or being heard Candy Chang

- Hands on creative practices – stories with a product or resource outcome e.g. sewing group creates a table of goodies to trade or sell

- Shared meals – stories and food!

- Sensory storytelling

- Bringing stories into everyday work practices. e.g. team meeting begins with a story

- Story walks – walking through spaces that belong to the story / soundscapes / giant books (involving community / creating ownership)

[The cookbook can be accessed here and Candy Chang’s work here]

Participants were also inspired by the idea of telling stories of collective endeavour – about a collection of moments in time – and stories written by unlikely collectives of people.

- Collective history of a period of time e.g. WWII Singapore

- Anthologies around a certain theme. e.g. place, identity, time

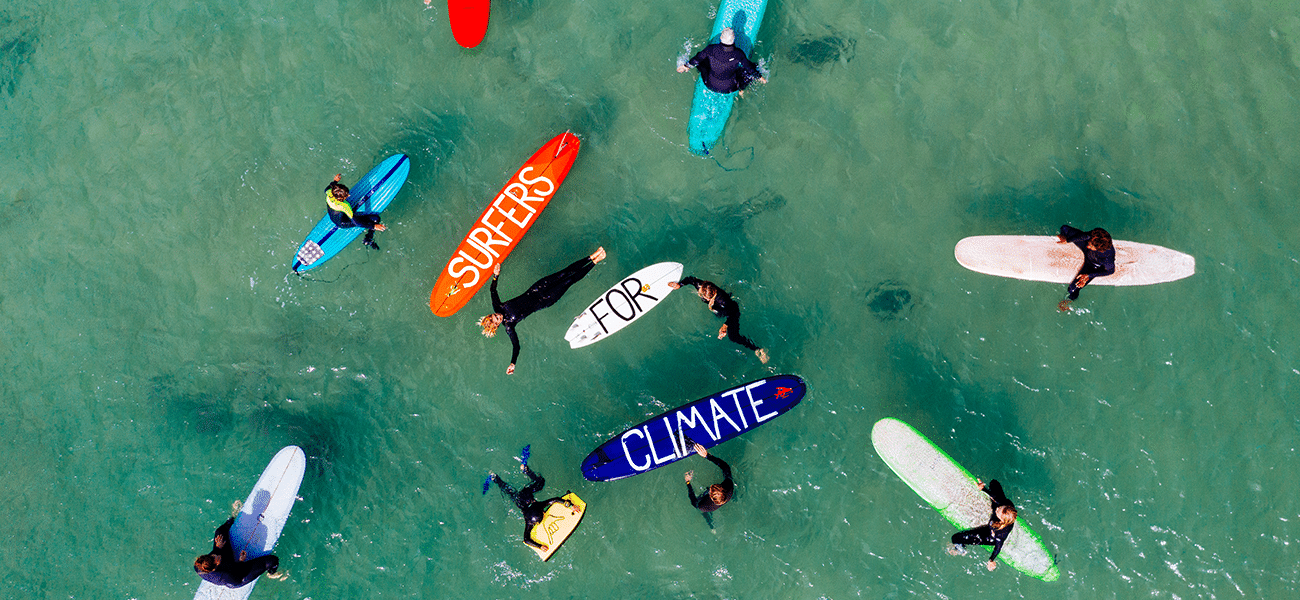

- Collective action on climate mitigation & biodiversity loss – Revive our wetlands

- Story co-authored by unlikely partners e.g. govt and community

- Chain stories, where story is explored from multiple perspectives – NOT MARKETING

chapter 13: How might stories be used?

People suggested that stories could be used as evidence of change…

- An “impact yarn gallery” – gathering community stories and displaying them in a gallery – this could be a meal, a written story, a visual story.

- I’m imagining funders coming to a community yarning circle rather than writing a boring report…

- To show how in a different way

- To be engaged with to understand the impact of interventions

…to encourage new perspectives…

- System stories – through other lenses, not making people the centre – other living things, materials, place to help shift perspectives.

- Orientation

- Getting out of formula story.. particularly on screen – ‘At Close Quarters’ using details and close ups rather than wide shots and general ‘perspectives’ with multiple tellers.

…as well as a way of building understanding and challenging traditional power dynamics…

- Ask funders to tell their story to community

- To unify around an idea across sectors – values rather than agenda driven

- To build common ground in community, shared understandings

…and as a form of healing.

- Catharsis

- To re-humanise disenfranchised community members / overcoming epistemological narratives

- To be/feel seen. To own experiences. To help other navigate similar challenges

chapter 14: What infrastructure is needed?

- A community story register to enable community members to contribute their stories, in their words, when it suits them

- Spaces for ephemeral storytelling – “open-mic night for people to share their stories”

- A “human library”

- A story database, where stories are captured and tagged

- Spaces to hear stories that come from unexpected places/people.

Burnie Works also shared their ideas around accredited Community Knowledge Collectors – a concept they are currently exploring. The theory of change is as follows:

IF…

Local people have the skills and capacity and are paid to contribute to collecting the information needed to understand the impact of Burnie Works’ collective change initiatives;

THEN…

Knowledge and information will be collected and communicated to help make sense of the population-level data, understand what is changing from a community perspective, and inform ongoing learning;

SO THAT…

Communities, backbone organisations, and funders have a robust evidence base for the impact of place-based collective change initiatives, such as Stronger Places, Stronger People (SPSP).

In addition, some suggestions were made around the different tools, equipment, ways of working, and spaces needed to support effective storytelling:

Tools/Frameworks:

- Narrative Change

- Impact Production

Spaces:

- Web

- Yarning Circles

- Story Walks

- Augmented Reality App

- Grassroots screening

Equipment/Resources:

- Visual Story Gear

- Travel

- Digital Development

Ways of Working:

- Urgent hope

- Listen to traditional Owners & supporting their stories to be told

- Plurality of perspectives and values

chapter 15: How will we get there?

Perhaps the most important part of this session was the how – we prompted people to think about what they would need to make their vision a reality. We asked, “to create and share more impactful stories of systems change, what will you need to…

- Encourage and build on?

- Overcome or address?

- Invest in?

- Further explore?”

Below captures some of the themes and ideas shared.

To achieve more impactful stories of systems change, we will need to encourage and build on…

- Encouraging senior people to recognise the value of stories

- Supporting funders and community members to value different ways of telling stories, e.g. dioramas

- Making it more the norm to give people thinking/creating/processing time to develop stories and connections to broader narrative

- Budgets which recognise the importance of storytelling

- Encouraging recognition for the value of different ways of knowing and understanding

- Helping people to see storytelling as being at the heart of any collective, organisation, business or department

- Better understanding about the role of story and narrative practice

To achieve more impactful stories of systems change, we will need to overcome and address…

- Bias in how stories are captured and told (i.e. whose voices are heard, centred, etc)

- Bias towards quantitative data and the scientific method (particularly by government and funders) and the simplistic binary that if the scientific method is “a good way of understanding”, then storytelling must be “a bad way of understanding” (or vice versa!)

- Managing dominant voices

- Moving away from “hero” stories towards shared stories and collective stories of change

- People not seeing themselves in narratives about change

- The idea that stories are static and “finished”, rather than things which evolve over time

- An imagination deficit – “I have found the greatest challenge is people having imagination for things outside of what they know. It’s an important social and cultural muscle that needs attention and investment.”

To achieve more impactful stories of systems change, we will need to invest in…

- Building storytelling skills in backbone teams and communities (e.g. through workshops, training, etc)

- Funding dedicated storytellers and/or storytelling teams (particularly local storytellers)

- One suggestion was to create a network of embedded storytellers in the community, supported by professional storytellers and each other. Concentrate it in 4-5 communities as a trial/proof of concept for 2 years and see what happens…

- Creating Communities of Practice and mentors for community storytellers

- Designing sustainable accreditation pathways and funding models for Community Knowledge Collectors

- Supporting listeners and storytellers to work together – people who tell great stories aren’t necessarily the best listeners

- Understanding effective ways to weave together qualitative and quantitative insights

- Technologies to support both the creation and the dissemination of stories

- Telling new kinds of stories, for example about partnerships and relationships

- Backbone team members seeing a core part of their role as being about capturing and sharing stories

- Building trust and psychological safety

- Hearing the voices of children and young people

- Storytelling collectives who share ideas and resources and are cross-sectoral

- Building understanding of storytelling traditions across different cultures and demographics

To achieve more impactful stories of systems change, we will need to further explore…

- At what stage of a process are stories best told?

- How can we best understand the gaps and biases that people are experiencing?

- How can we use stories to grow investment?

- What is the role of experts?

- How can a community own the distribution mechanisms – community newspapers/TV/radio – and how can these be structured so that old ways of gatekeeping are avoided?

- How can we use stories to shift power?

This branch of the story resulted in a range of ideas around how to better enable those involved in community-led systems change initiatives to tell compelling stories about the nature and impact of their work.

Some of the ideas relate to the supply side (how to generate better stories), while others focus on the demand side (how to increase the likelihood that the stories are heard). The fact that both sides of this equation need our attention and energy is a key insight from this work.

chapter 16: Where to from here?

While this report marks the end of this phase of work, it is not the end of the story. This report is a chapter – a seedling – from which more chapters and branches will grow.

The report captures and synthesises what we’ve heard to date and offers an ambitious but practical list of priority actions to explore, which include:

- Building understanding of storytelling traditions across different cultures and demographics

- Increasing the value of different ways of telling stories of change

- Challenging the bias towards quantitative data and the scientific method

- Understanding effective ways to weave together qualitative and quantitative insights

- Creating Communities of Practice and mentors for community storytellers

We approached this work with the intention to generate value beyond the report. We know that the conversations we’ve had over the past several months through listening sessions and workshops have already generated new ideas and opportunities for those who’ve participated.

To extend this further we will be exploring a second phase of this work, which will focus on translating some of the ideas generated from this phase into practical action.

As we close this chapter and start a new one, we are looking for partners who are interested in supporting these emergent stories and branches to grow, so that we can better enable and celebrate community-led systems change work.

If you are part of a backbone team or a government department, or a community storyteller, a philanthropist or organisation interested in contributing to growing:

- stories that can reshape systems

- stories that deepen understanding and build connections

- stories that showcase change

“…in the end, stories are about one person saying to another: This is the way it feels to me. Can you understand what I’m saying? Does it also feel this way to you?”

Kazuo Ishiguro

Resources

Theory and ideas that have shaped our thinking:

- The Narrative Initiative’s report, Toward New Gravity, captures the insights from their 2017 listening tour of over 100 experts, innovators and visionaries from a range of disciplines and communities, working at the intersection of social justice and narrative change

- In Are You Really Listening?, Kevin Sharer and Adam Bryant share how leaders can actively create a more expansive “listening ecosystem”

- Dr Claire Craig and Dr Sarah Dillon have written an article on Storylistening, which explores why narrative evidence matters for public reasoning

- The Role of Narrative Change in Collective Action – described as “a masterclass on narrative” from the 2021 Collective Impact Summit

- Sam Rye’s article Metaphors of Change explores how metaphors shape our understanding of the world

Useful toolkits/how-to’s:

- The Art of Storytelling – a lesson hosted by Pixar directors and story artists about how they got their start and what stories inspire them, and how to think about the stories you might want to tell

- Old Fire Station has produced a guide to using storytelling to evaluate impact, which details their Storytelling Methodology and the seven steps to storytelling

- The National Lottery Fund’s Storytelling Tool – designed to help identify and connect themes and patterns between shared experiences of the pandemic to tell the story of communities together

- And then what happened? Storytelling Card Deck by Libby Heasman Design – designed to assist people in crafting and telling compelling stories

- NPR’s Guide to building immersive storytelling projects

Inspiring stories

- In My Blood It Runs is an extraordinary vision of what it looks like to privilege First Nations perspectives

- Village Connect in Logan is a 9-minute video that tells the story of systems change – the establishment of communitybased maternity hubs – from the community’s perspective. Content warning – there are very sad stories of babies dying at birth

- The Other Others is a podcast by Tyson Yunkaporta, an academic, author, arts critic, and researcher who belongs to the Apalech Clan in far north Queensland. In the episode, Psycho-technologies of Memory, Tyson talks to Lynne Kelly (author of The Memory Code and Memory Craft) about place-based, storied memorisation techniques used around the world by cultures retaining pre-industrial traditions

- Songlines is a 5-minute, virtual reality-ready YouTube video

- Indigenous storytelling as a political lens is a TEDx talk by Tai Simpson. Tai works in antiracism education and community organising. She calls on her non-native audience to embody “old ways” when voting, teaching, and living in the world

- “Making Burnie” – A Tasmanian Story of Collective Impact is a 3-minute video by Digital Storytellers

- Building Bourke – The Story of Maranguka and Just Reinvest in Bourke is another great video by Digital Storytellers

- Narrative is one of the most powerfully motivating human forces. In his TEDx talk, filmmaker J. Christian Jensen reveals how the same emotional forces that thrust us forward in a good film can propel us to do remarkable things

- How stories shape our minds is a 4-minute YouTube video by BBC Ideas. It explores the science of storytelling and the power of stories to share our minds – how stories make us human, why stories matter, and why stories are important in our lives

- Fierce Girls is a series of short-form ABC podcasts written and narrated by girls aged 8 to 11. Having young girls tell the stories of women’s achievements is a great way to bring a fresh and interesting take on sharing stories

- Linaya is an award-winning documentary animated film about an original African tale created by orphaned children in Eswatini. A beautiful example of co-creation and the power of storytelling

- Burnie Works has collated a series of case studies which highlight the changes taking place in their community – both in terms of more traditional metrics of change and as changes taking place in how the community is working together

Organisations doing storytelling work

- Desert Pea Media works with First Nations young people and their communities to create social change through collaborative storytelling

- Playback Theatre is a Sydney organisation that creates engaging, interactive and transformative theatre. In their shows, they invite stories from the audience and use them to create experiential performances – stories are transformed into moving, funny and beautiful improvised theatre that illuminates the human condition

- Common Ground is a First Nationsled not-for-profit working to shape a society that centres First Nations people by amplifying knowledge, cultures and stories

- The Human Library is an organisation and movement that first started in Copenhagen in 2000. It aims to address people’s prejudices by helping them to talk to those they would not normally meet. The organisation uses a library analogy of lending people rather than books. There are a few human libraries popping up in Australia as well!

- Harvard’s Nieman Lab looks at literary journalism – the use of storydelivery techniques usually found in fiction applied to non-fictional work. A good resource to start (the rabbit hole) with is Storyboard 75 – a “best-of” list of craft essays, interviews, how-to’s and recommended reading, as well as analyses and author line-by-lines

- Esem Projects uses experiential media to cocreate placebased stories in partnership with communities

- Wakulda: Weaving our Stories as One is a 10-minute semi-permanent digital projection commissioned by Port Macquarie- Hastings Council in 2020 to mark the bicentenary of the colonial settlement of Port Macquarie, while recognising the experience of dispossession among Birpai people. Meaning “as one” in Gathang, the language of the Birpai people, Wakulda centres on telling the stories of all who have walked this place

- Esem Projects also run STORYBOX Places to deliver participatory storytelling platforms in public spaces

- This includes the Tiny Stories program, which allows anyone to share a moment in their life for exhibition/animation on STORYBOX and includes curated call-outs

Conversation guide for listening sessions

We used these questions as a basis for the conversation, but used them as a guide rather than a strict list we had to adhere to. We allowed the conversations to follow their own course, meaning that in some conversations we worked our way through all of these questions, whereas in other conversations we may only have worked through one or two, with the rest of the conversation emerging organically from there.

You’ll notice that we didn’t use the term “systems change”. This was a deliberate decision because we know this language can feel confusing and intimidating, and we realised that we could have the conversations we needed and wanted to have without using the language of systems change at all!

- Are stories important in creating change? Why or why not?

- What does good storytelling look like?

- Do you tell stories about your community and/or your work within your community?

- What makes it hard to tell your community’s stories? (E.g. time, equipment, access to people who can tell the stories)

- Who would you like to hear your community’s stories?

− Are your stories reaching them?

− If not, what makes it hard for your stories to be heard? - Have you seen any good examples of storytelling in your community? What did you like about it?

- Could telling community stories could help get through hard parts of your work?

− If not, why not?

− If so, how? - If you do tell your community’s stories, how do you do this?

Storytelling Digests

Our Team Charter captured the idea that “the way we work is as important as the final product”. Given this, we wanted to make sure we were capturing the story of the project – ensuring we were sharing what we were learning along the way.

- One weekly project highlight – updating people about the progress of the project;

- Two quotes from interviews that stood out to us – allowing us to share some of the great insights from our listening sessions;

- Three great examples of storytelling – recommended by interviewees and discovered throughout the project.

Further acknowledgements

The Storytelling for Systems Change project would not be what it is without the contributions of many. We are grateful for the generosity people showed in sharing their time, thoughts and ideas freely, and working collaboratively in deep consideration of what storytelling is and what it could be.

We appreciate their ability to consider what is needed to support the telling of stories in a multitude of places and a multitude of ways. This project would not have been possible without understanding that stories are intrinsically linked to the communities that tell them.

We want to thank the following people for their work on this project, for their drive to help support the creating, telling and sharing of stories that can reach out into the world to connect change back to their home:

- Abigail Graham – Latrobe Valley Authority

- Alistair Ferguson – Maranguka

- Amy Denmeade – Crawford School of Public Policy

- Bre MacFarlane – Home Base Mildura

- Catherine Thompson – Hands Up Mallee

- Dalit Kaplan – Storywell

- Dean Wickham – Hands Up Mallee

- Fiona Merlin – Hands Up Mallee

- Jane Anderson – Latrobe Valley Health Advocate

- Kerry Graham – Collaboration for Impact

- Kylie Burgess – Burnie Works

- Lucy Taylor – Burnie Works

- Lucy Tierney – Just Reinvest NSW

- Melanie Corona, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Early Years Education Worker – Department of Education, Tasmania

- Nicole Mekler – Just Reinvest NSW

- Nikita Hart – Connected Beginnings

- Pippa Bailey – ChangeFest

- Rachel Longeri – Sunraysia Community Health Services

- Rona Glynn-McDonald – Common Ground

- Rowena Cann – Latrobe Valley Authority

- Sam Rye – Conservation Volunteers Australia

- Sarah Barns – Esem Projects / Storybox

- Sarah Marshall – Communities Tasmania

- Shandel Pile – Burnie Community House

- Simon Goff – Purpose

- Skye Trudgett – National Centre for Indigenous Excellence

- Tyson Yunkaporta – Deakin University