The data collection technique was an unusual one that TAI refers to as “speed dating”, whereby small groups of students rotate through a series of adult facilitators who run brief “yarns” on a series of topics. Some of the results were very surprising indeed, with particularly strong responses around verbal instruction that will be of interest and benefit to all teachers.

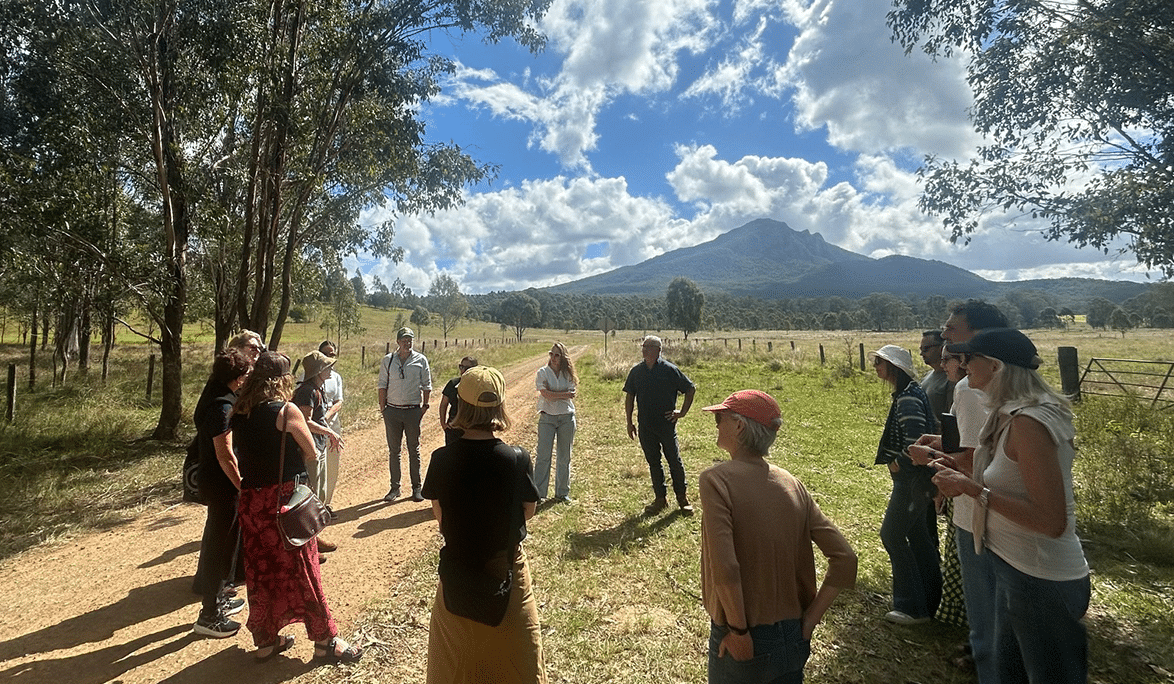

Many of the responses were aligned with the best international research in Aboriginal pedagogy, focusing on group discussion, narrative, land-based learning, hands-on activity, balancing communal and individual tasks, visual learning and purposeful/contextualised learning. The big surprise came with assertions around a preference for verbal instruction – but only very specific kinds of verbal instruction.

In general, these Koori students stated that they usually fell asleep during verbal instruction, but that their favourite learning events occurred when interactive and dynamic teachers were delivering the same. “It’s not the talking; it’s the way of talking!” They asserted that passion and “interactivity” were the keys to successful verbal instruction. The teacher must be interested, passionate and excited about the topic, so that “you can tell they want to be there.” Their favourite learning experience was a lesson on grammar that was delivered by a passionate and dynamic instructor.

Delivery is the key – it must be fast paced (but not rushed in terms of content), action-packed and full of variety in terms of tone, volume and emotion. Movement was a significant factor. Contrary to orthodox practice, these students asserted a preference for teachers who moved around the room constantly. They also emphasised the importance of using exaggerated hand gestures and body language. Humour was also flagged as a key element of successful instruction – when the group is laughing, the group is learning. They stated a preference for instruction that responded to their input and interest, with the teacher being happy to change the structure of the delivery from one moment to the next.

The instructor must be prepared to both review and preview ideas, to jump forwards and backwards in the planned sequence. Students like to have an overview of the content, with the most important points flagged before and during delivery and the discussion built around these key points. The group should be encouraged to find their way through the topic, with the teacher co-navigating the learning sequence, making sure students are both collaboratively and individually making connections between the main ideas.

In addition to actively shaping the discussion and exploring ideas, the students also like to “have something to do to stop daydreaming”, which may involve taking notes or visually mapping ideas.

Above all, the subject matter must be interesting. The students expressed a unanimous disdain for presentation of plain facts – they asserted that “it has to have a meaning behind it.” For example, they found a session on iconography fascinating, whereas a regular English lesson explaining the elements of visual text analysis would be considered boring. They also demanded that content be grounded in documented, real-life events. There was a strong desire expressed for evidence and proof of knowledge. Proof must be demonstrated either through logic or practical testing (e.g. measuring students’ heart rates to test the assertion that fluorescent lighting elicits a flight/fight response in teen males). Students expressed a need to be able to validate or discredit claims made by the teacher by interrogating or testing those claims. The need to cite sources was also important – “Who? Who says this?”

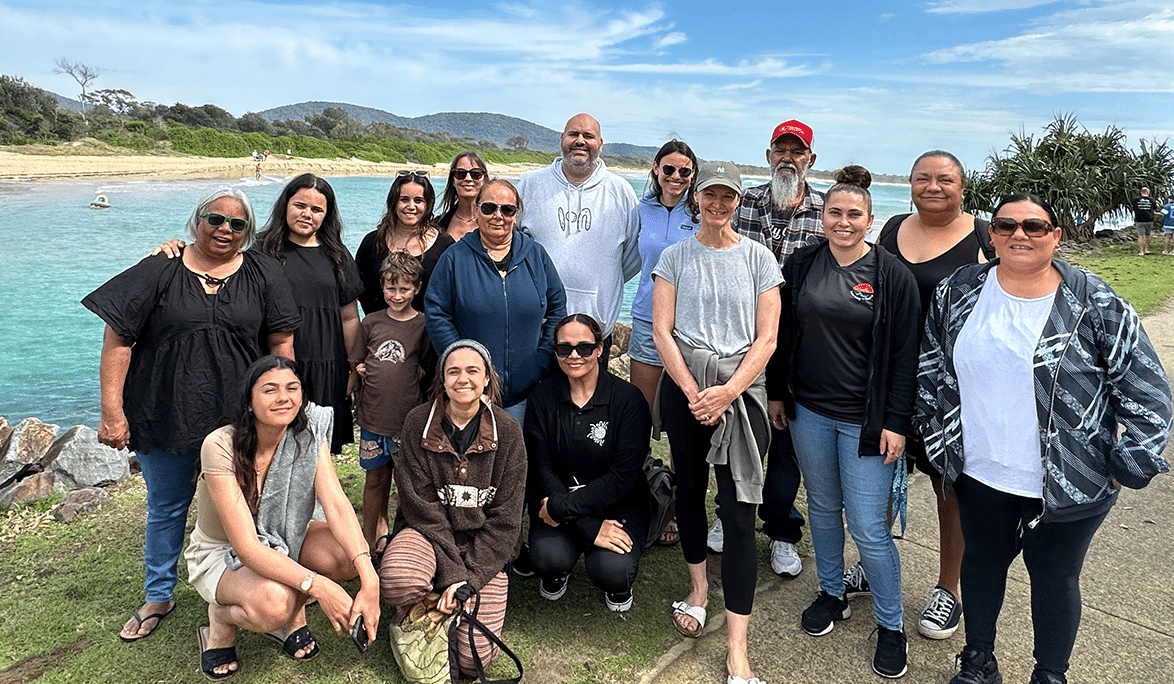

Finally, a word on culture. The students seemed to value culture more as an organising principle or ethical standpoint than as a topic for study, stating this as a preference for culture as the “why” rather than the “what”. They said that culture needs to give extra meaning to the learning, a reason for learning in the first place. They cited cultural metaphors (“this is like this”) and narratives as good ways to assist in the understanding of new concepts. “But the link must be clear – when it isn’t a real link, when the message is not clear, it’s not good.” They said they were often confused by the cultural content presented in mainstream learning, that the culture must support the learning process rather than just provide the topic.

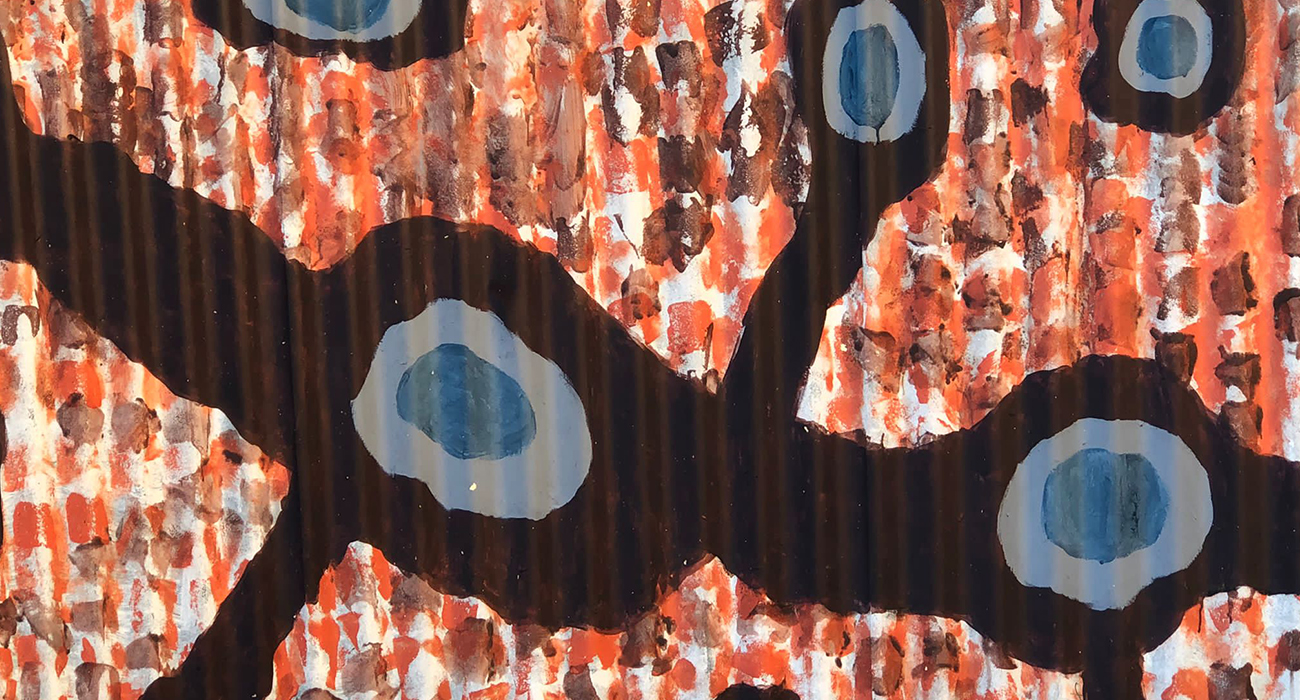

One example they repeatedly referred to was a TAI session on Aboriginal memorisation techniques, in which they converted some lecture notes into symbols and burnt these images onto message sticks. A year later they still have those message sticks as a “daily reminder” of what they learned in that lecture.

From Guest Blogger – Dr Tyson Yunkaporta | The Aspiration Initiative Aboriginal Education Specialist

From Guest Blogger – Dr Tyson Yunkaporta | The Aspiration Initiative Aboriginal Education Specialist

Tyson Kaawoppa Yunkaporta is a Bama of Nunga and Koori descent with cultural ties to Mardi mobs in Western NSW. With an accomplished career in both mainstream and Aboriginal community contexts, Tyson has worked in K-12 classrooms, as a university lecturer, as a senior executive officer in the Department of Education and as an Aboriginal pedagogy mentor. In 2009, Tyson completed his PhD in Education at James Cook University, where he was awarded the medal for excellence with his thesis titled “Aboriginal Pedagogies at the Cultural Interface.” As The Aspiration Initiative’s (TAI) Aboriginal Education Specialist, Tyson works on the overall development and structure of TAI’s pedagogy and curriculum. On camps, he takes on key roles in teaching and cultural facilitation, with both students and teachers. He continues to play a fundamental role in community relationship building and consultation.