Fast-tracking from school to work

Australia ranked second bottom on the OECD league table on vocational preparation. It was amid this arid landscape that TRAC emerged. The Training for Retail and Commerce program was developed by the Dusseldorp Skills Forum in 1989 to bridge the gap between the worlds of school and work and improve young Australians’ preparation for working life.

TRAC was a pioneering program. For the first time, vocational subjects with formally accredited workplace learning were available to students in Years 11 and 12. It was a joint partnership between schools, workplaces and TAFE which put high school students into on-the-job workplace training one day each week.

TRAC was a success and in 1994 the Federal Government launched the Australian Student Traineeship Foundation (ASTF) as mechanism for mainstreaming structured workplace learning in schools. The accompanying VET (Vocational Education and Training) subjects still run in schools across Australia.

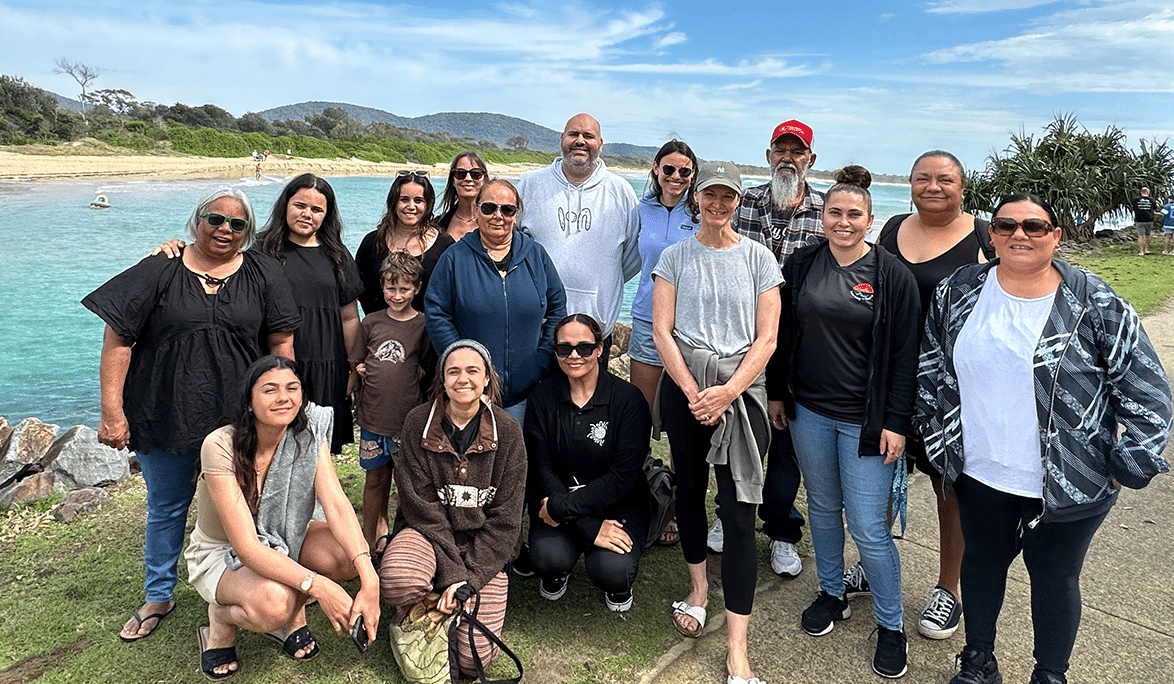

From right to left: Kerrie Stevens, Tjerk Dusseldorp, former NSW Government Minister and WorldSkills supporter Milton Morris, and Kay Sharpe, CEO of the Hunter Valley training company.

How TRAC unfolded

TRAC was the Dusseldorp Skills Forum’s first project. Following the triumph at the international Youth Skill Olympics the previous year, WorldSkill Australia’s founder Tjerk Dusseldorp and project manager Kerrie Stevens focused the energies of the Forum on bringing innovation to vocational education in Australia. The duo were joined by the Forum’s first full-time employee, Richard Sweet, a renowned analyst with a track-record for improving vocational training, who later went on to work at the OECD in Europe. As outlined in Jane Figgis’ 2006 report Looking Back at TRAC, a lack of relevant vocational training in schools had been widely recognised at the time, but unsuccessfully addressed. Tjerk and Richard studied vocational models that had withered, and noted that failings included their “top down” approach, with little connection to employers or students. Given there was a need for a program that worked, TRAC spread rapidly. It was initially replicated locally in regional NSW, then across Tasmania and South Australia, and most other states and territories. “TRAC was the vanguard,” Kerrie said. “It really led the way. It inspired the Department of Education into offering more appropriate learning for the students who weren’t going to follow an academic career.”

Piloting TRAC: Newcastle

The Hunter region was chosen as the pilot site. As well as being a microcosm of every social economic stratum, and a mix of nationalities, at the time the Hunter was feeling the effects of major steelworks employer BHP pulling out of the region, which would soon result in an employee shift to the service industries. Of the numerous TRAC pilots in operation, the first one to transition to an “official” program was in 1991 in the Newcastle region, as shown on NBN news at the time. It comprised 37 Year 11 students from the Hunter Region. TRAC had a number of components. Each program had employers who offered placements to students, paid a fee to the TRAC program for the placement, and nominated workplace supervisors to train and assess the student. TRAC was kickstarting Australia into emulating European practice, providing multiple pathways from school into the workforce. In the early 1980s Lesley Tobin joined the Forum’s team to manage the growing number of pilots and programs across Australia. Lesley worked with the Forum for the next 18 years, spearheading the Australian Youth Mentoring Network project and the Learning Choices expos.

Growth and Devolution

By 1992, TRAC programs were operating in regions with high youth unemployment including Tamworth, Central Coast and Sydney’s Northern Beaches. By 1995, there were 80 TRAC sites with 2,000 students operating across Australia.

This overwhelming success posed a small problem for the Forum; it had never intended being an operational unit. A strategy to embed TRAC in the system began.

Simultaneously, the Federal Government was interested; here was a pilot scheme that enabled successful transition to the workforce, especially for areas with high youth unemployment.

Discussions ensued, and senior researcher Richard Sweet was taken into the Education Department by then Minister Simon Crean to collaboratively develop a brief as to what the new organisation would look like and how it would work.

The ASTF (Australian Student Traineeship Foundation) was announced as an initiative in Keating’s Working Nation. It was an independent, Government-funded structure, with its own board, operational unit, and was established to embed structured workplace learning across the country.

The new foundation’s charter was based on TRAC’s key principles, and was set up as a freestanding entity. In 1994 the federal government committed $38 million over four years to embed quality Vocational Education and Training in schools. The foundation’s independent funding enabled school managers to make decisions, to structure workplace learning and to develop links with the community and businesses. John Goodman, a founding Forum board member, was the ASTF board’s first chair.

Prime Minister Paul Keating officially launched the ASTF in 1994 in Gosford, on the Central Coast of NSW, acknowledging the roots of ASTF in the TRAC program.

“The reason why the Central Coast TRAC program succeeds,” Mr Keating said in his speech, “why all of the TRAC students who left school last year are in full-time jobs, is because of the combined efforts of the schools, the students, TAFE, industry and the wider community.”

The ASTF was a well-oiled machine. Former Forum consultant Eric Sodoti recalls: “Within three or four years about 11 per cent of students across Australia were learning in a structured work place. It was extraordinary.”

When the Howard Government was elected in 1996, Eric recalled that only two of the Keating Government’s Working Nations’ initiatives survived: the Jobs Pathway program and the ASTF.

Also in 1994, the NSW Board of Studies produced its own Content Endorsed Courses for vocational strands (retail, office and hospitality), and TRAC was recognised as a model for bridging the gap between school and work using structured work placements.

In 1995, the VET Network was established, a cohort of teachers, trainers, career advisers and others committed to vocational learning and youth transition, which was strongly influenced by the TRAC experience.

In 1996 the Dusseldorp Skills Forum passed final responsibility for the TRAC program onto state-based committees and the ASTF.

The legacy of TRAC

“Standing back now, with the benefit of time,” Kerrie Stevens said in 2014, “I am far more aware of the impact that it had, than when I was involved. It has not gone away, the concepts are still there in what the students are doing in schools. TRAC really changed the system.”

For students who weren’t academically inclined to start off with, TRAC gave them a pathway that was incredibly valid, Kerrie Stevens said. “They later reflected they were staying at school for a purpose. TRAC let them develop some core transportable skills. They would take them on a pathway out of school and it would help them in a future”.

TRAC changed lives: it lifted the aspirations of many young people drifting through senior high school years. It created a contagious sense of purpose in its participants, leaders and administrators, and left a legacy of VET in high schools.

TRAC paved the way for the national roll out of VET in schools across Australia.

“The result being,” said Tjerk Dusseldorp, that: “70% or so of all young Australians now, in schooling, have an experience beyond the premises of the school.”

For more information see Jane Figgis’ 2006 report Looking back at TRAC.