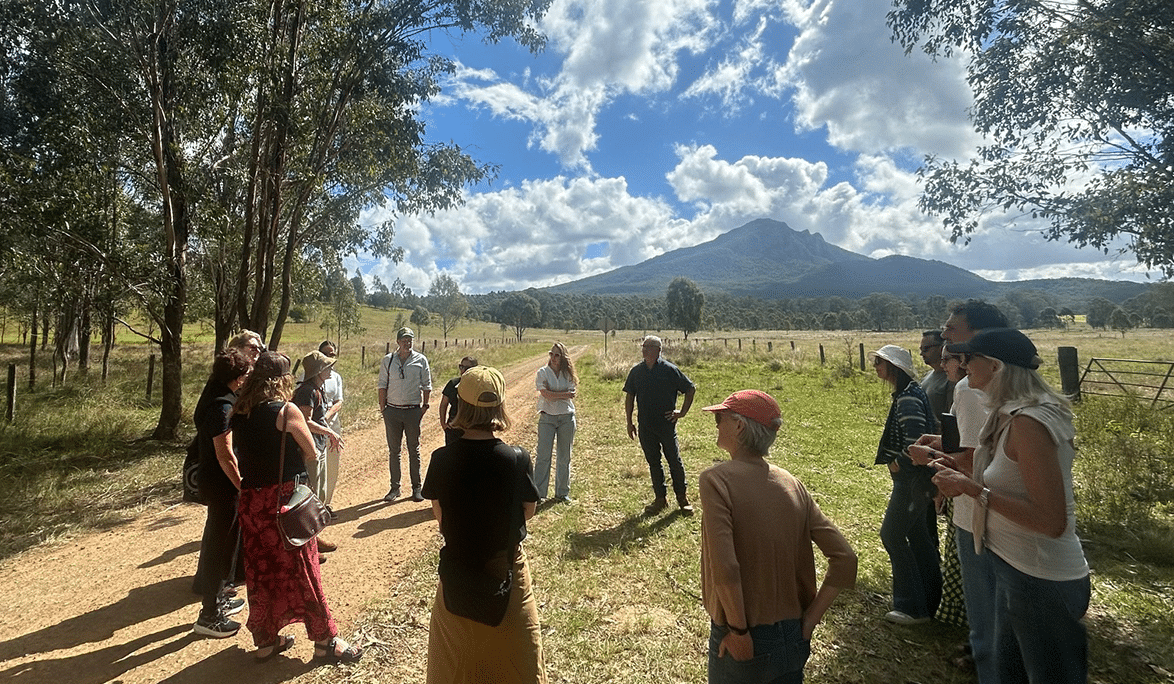

“I want to see this land repopulated with the plants of this place,” says Pete Cooley, founder of IndigiGrow. “It’s not just about putting plants in the ground—it’s about regenerating an entire landscape, culturally and ecologically. That’s our responsibility.”

From mechanics to bush foods

Pete’s journey into horticulture wasn’t a typical one. He worked as a mechanic for 20 years and then started his own business First Hand Solutions Aboriginal Corporation before a persistent suggestion from his partner Sarah opened a new door. “She kept saying, ‘You should look at what is happening with native foods.’ I didn’t give it much thought at first—it just wasn’t something that was on my radar,” Pete admits.

But a visit to a finger lime farm changed everything. “I saw rows of finger limes, thousands of them, all being grown commercially, and exported internationally at quite a profit. I could see that the bush foods industry was being built on Aboriginal knowledge, while we made up less than 2% of it. That didn’t sit well with me.”

What followed was a period of learning, trial, and error. Pete completed a certificate course in bush foods horticulture and started to build a model that went beyond commercial goals. “I didn’t want to just jump into business for profit. I wanted to create something that aligned with our cultural responsibility to care for Country.”

Reviving a lost plant: The Bush Lolly

One of IndigiGrow’s most significant successes has been the revival of the “five corners” plant, widely known in the community as the bush lolly. Pete was introduced to the plant as a child but hadn’t seen its fruit for decades. That changed when he discovered it flowering again on a local headland.

“I stood there staring at it. When I tasted the fruit, it was sweet and sharp, just as I remembered. Straight away, I knew why Elders had called it a bush lolly,” Pete says.

Determined to bring the plant back, Pete set out to propagate it, despite being told by experts that it was too difficult. “We took 100 cuttings and lost 99 of them. But one survived – and that one was all we needed to know it could be done.”

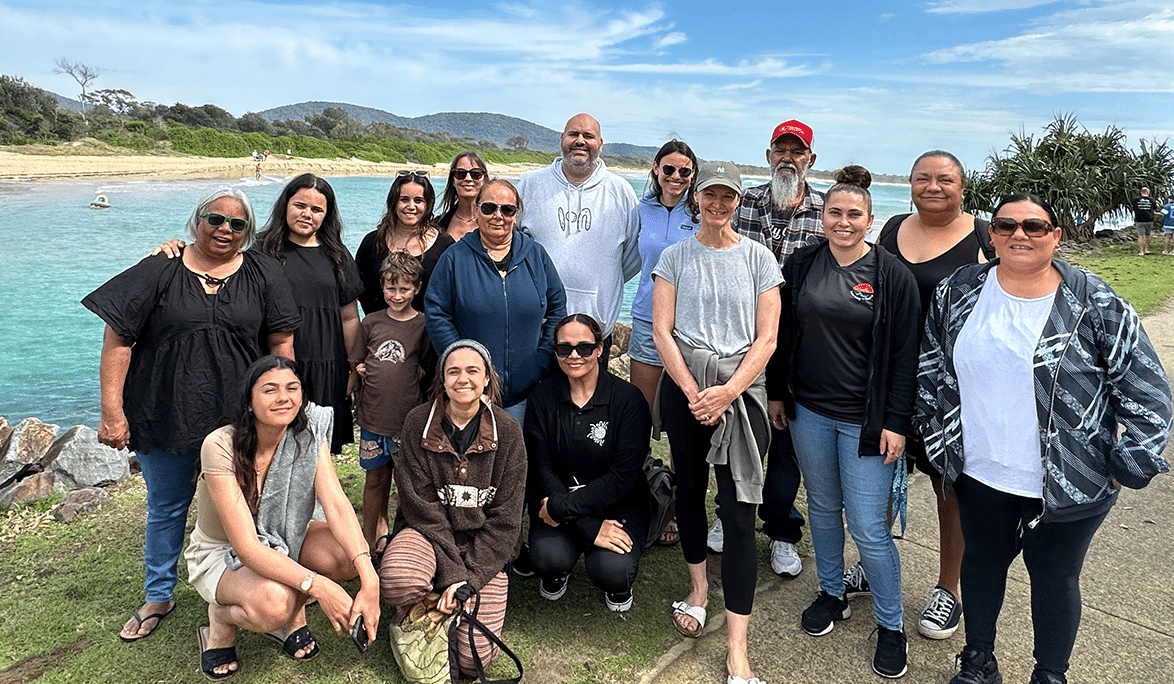

Over several years, Pete and his team refined their methods, increasing the survival rate from just 1% to over 90%. In 2023, during NAIDOC Week, IndigiGrow gifted 2,000 bush lolly plants to Elders and community members at La Perouse—a moment Pete describes as a “big milestone.”

“That was the first time our community had planted five corners back on Country. For the Elders, many of whom hadn’t tasted the fruit for 60 years, it was emotional. It was about reconnecting with something that had always been part of who we are.”

Growing more than plants

Raymond Sarich, one of Indigigrow’s five apprentices, grew up in La Perouse and has watched the nursery’s journey closely. “I always kept an eye on what Pete was doing, and eventually I reached out and said I’d love to do an apprenticeship,” Raymond explains.

For him, the nursery feels like a natural fit. “It just feels like home. Every day’s different, which keeps it interesting. I really like working with the sunshine wattle—Acacia Terminalis. It’s always got new growth, and when it flowers, the yellow is amazing.”

Raymond also enjoys working with bush foods. “Finger limes are a favourite. I love them fresh, but I also use them on oysters instead of lemon—it’s a great combination.”

He sees the deeper purpose of the work too. “A lot of the knowledge about bush foods and native plants has been lost over time, especially in the last 50 or 60 years. What we’re doing here is helping to bring that back and protect what’s left.”

IndigiGrow’s Aboriginal apprentices are working to save critically endangered plants known as the Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub (ESBS). The ESBS is an endangered ecological scrub, heath and woodland vegetation community found around the coastal suburbs of Sydney. The community once grew widely on about 5,300 hectares of land between North Head and Botany Bay, but just three per cent of the scrub remains today.

A pathway to sustainability

Pete is clear that IndigiGrow’s work isn’t just about plants—it’s about shifting systems for cultural and ecological sustainability. “We are heading down a path of erosion and there is a tipping point that we just don’t come back from. We have to turn around and start a regeneration that leads us in the opposite direction. We need councils, landscapers, and developers to rethink what they’re planting. Local, endemic species should be the starting point. It’s simple: if you plant what belongs here, you create a sustainable environment.”

He explains that many residents might want to plant native species but can’t find them in nurseries. “It’s a supply chain issue. Nurseries don’t grow what there’s no demand for, and councils aren’t pushing for local species. It’s a cycle that keeps repeating itself.”

Pete points out that this is more than just an environmental issue. “We’re spending billions trying to eradicate feral species that have escaped from people’s gardens, while our local species are disappearing. It’s not sustainable.”

Why First Nations-led matters

For Pete, the leadership of Aboriginal people is central to IndigiGrow’s success. “We’re not just growing plants because it’s good business. We have thousands of years of connection to these species. That connection matters—it shapes how we care for the plants and the land.”

He also notes that reviving threatened species requires patience and dedication. “Commercial nurseries won’t take on these plants because they’re too hard and not profitable. But for us it’s about cultural survival and environmental health. That requires an entirely different approach that allows for time on Country to learn, educate and connect.”

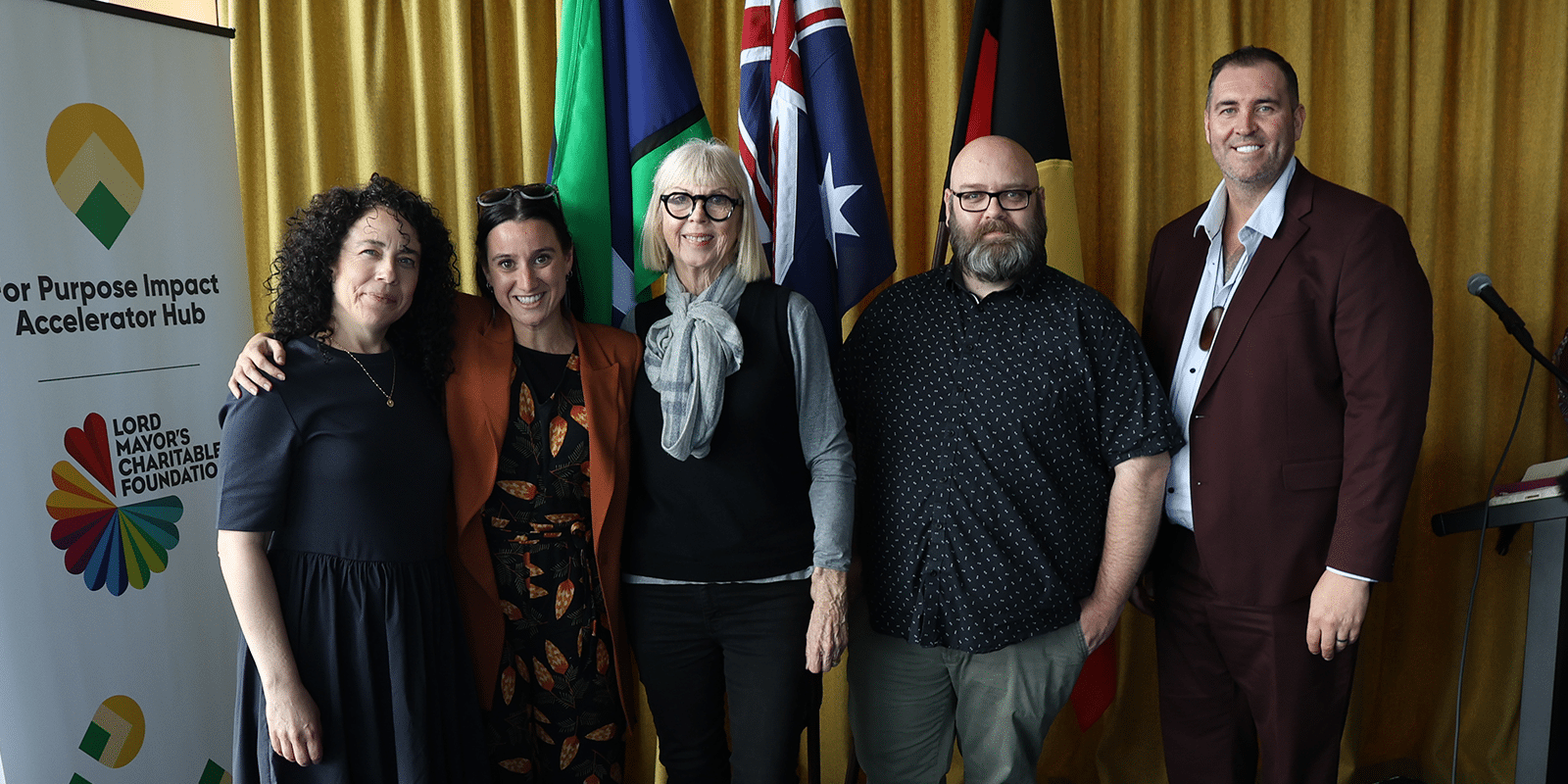

A social enterprise with purpose

IndigiGrow is a not-for-profit social enterprise, blending horticulture with cultural education and employment. “We’ve created a model where young Aboriginal people are leading the revival of threatened species and increasing biodiversity,” Pete says. “It’s their work that’s making a real impact.”

The nursery generates income through plant sales, but Pete knows that’s not enough to fund the deeper, knowledge work. “We’ve started opening up to philanthropic and corporate partnerships. It’s about more than just volunteering – we need long-term investment so we can keep doing this work properly.”

Looking ahead

Pete believes there’s growing awareness about the importance of native plants and First Nations-led land care, but there’s still a long way to go. “The work we’re doing is about making sure these plants, and the knowledge that goes with them, are still here for the next generations.”

Raymond agrees. “This isn’t just about today. It’s about keeping that knowledge alive and making sure these plants are here long into the future.”

Learn more about the work of IndigiGrow and how you can get involved here.